0%

Ownership. Cattle farms and thousands of kilometres of fences slice up the desert that surrounds the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. The San, Bushmen, or Basarwa people have lived in the Kalahari for over 30,000 years. Today these desert-dwelling masters of adaptation need permission from landowners to forage for veld food, collect firewood, or visit relatives who work on the farms.

Dislocation from their desert and disdain by mainstream society have made the San sick and maginalized. In the early 1980’s government policy began to reflect integration of the Bushmen into modern society. In defence of his government’s systematic relocation of the San people from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, President Festus Mogae asked: "How can we continue to have Stone Age creatures, in an age of computers?" These "creatures" however had no desire to move. The President’s remark reflects a legacy of racism. Before independence, Bushmen were often used as forced labour on Tswana ranches.

Farmworkers. This Bushman family works on a farm near Ghanzi, the frontier town in the western Kalahari. They dry Kudu meat, called 'biltong'. The San are regarded by the ruling Tswana tribe as "people without cattle", in a country where stealing a cow brings a mandatory 10-year prison sentence and where labour laws to protect farm workers are non-existent. Landowners, diamond miners, and politicians are frequently the same people in Botswana.

Nanke’s cousins. Bushmen are one of the oldest cultures on the planet. Today, cattle ranching, diamond mining, . cultural genocide, AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria have driven them to the edge of extinction. Thousands have been forcibly removed (water wells and homes destroyed) from their land and animals, to languish in what the Botswana government calls, in the name of modern services and education, "new settlements. " Many San call them "places of death". Nanke’s cousin pauses from her washing. They live in a mud house with a sand floor. They are grandparents who care for two small children who were both infected with AIDS at birth. The mother, their daughter, died a year ago.

Nanke’s home. Lennah Nanke Mothimit, 38, visits with her sister, Anna. Nanke contracted AIDS in 1999 from a rapist. She is one of the few women in D’Kar who is open about her HIV status. She is currently estranged from her mother, ostracized by the church, and abandoned by the fathers of her children. "My mother is embarrassed and doesn’t want to face thinking about the time when I lay down." Nanke makes money by selling home-made beer and cleaning a foreign aid worker’s house once a week. She has two grown daughters, and two babies who live with her in her one-room tin shack. She laughs when I ask, "Where are the fathers?" The monthly government food ration of mealie meal, oil and oranges, is never enough.

Ghanzi ghetto. For over a decade San people have been squatting on the outskirts of Ghanzi. They live in tin shacks constructed from recycled and waste material. They come with nothing from the villages and farms, hoping for something that never comes. Children raise children because both parents and grandparents have died of AIDS.

Shebeen in Ghanzi. On the outskirts of Ghanzi is a ghetto of hundreds of plastic, tin and cardboard shelters with no water or sewage services. Local 'shebeens' supply the only entertainment.

"Cut off by accumulated knowledge from the heart of their own living experience, he moves among comfortable rubble of material possession, alone and unbelonging, sick, poor, starved of meaning" Laurens van der Post, "The Heart of the Hunter".

Ghanzi ghetto. The highest-risk groups in Botswana are disempowered women; marginalized youth; street, sex, and migrant workers; the displaced; and refugees. The Bushmen fit into all these categories. Desperation lures young San women/girls to men with money. They charge 50 pula ($10) for sex with a condom and 200 pula ($40) without a condom.

Shebeen, Ghanzi ghetto. In the 1980s the South African military hired Bushmen out of the Kalahari as trackers in their war with Angola. The survivors returned to the desert with money, and then bottle (liquor) stores followed. Before 1998, the Trans Kalahari Highway was a rough sand track to Ghanzi, which was a remote and forgotten cattle post and very difficult to reach.

Ghanzi health post. There is no shortage of AIDS awareness signs and condom distribution boxes in Botswana. The message is clear. What is not clear is who is listening. "Changing behaviour is the challenge, " says Cheryl Arnison, a Canadian AIDS nurse with 7 years experience in Botswana, who works in ARV (anti-retroviral) clinics. She estimates that 40,000 people are being treated with ARVs, and that another 600,000 people require treatment.

D’kar funeral. The burial near D’Kar of a young woman and her boyfriend. They were living together. He went to a party, got drunk, and slept with another woman, who is HIV positive. When he returned his girlfriend refused to sleep with him until he got tested. He broke her neck and then hanged himself. People in D’Kar call it a crime of passion. At the funeral the missionary preacher blames alcohol for the tragedy and proclaims abstention as the solution to the AIDS pandemic.

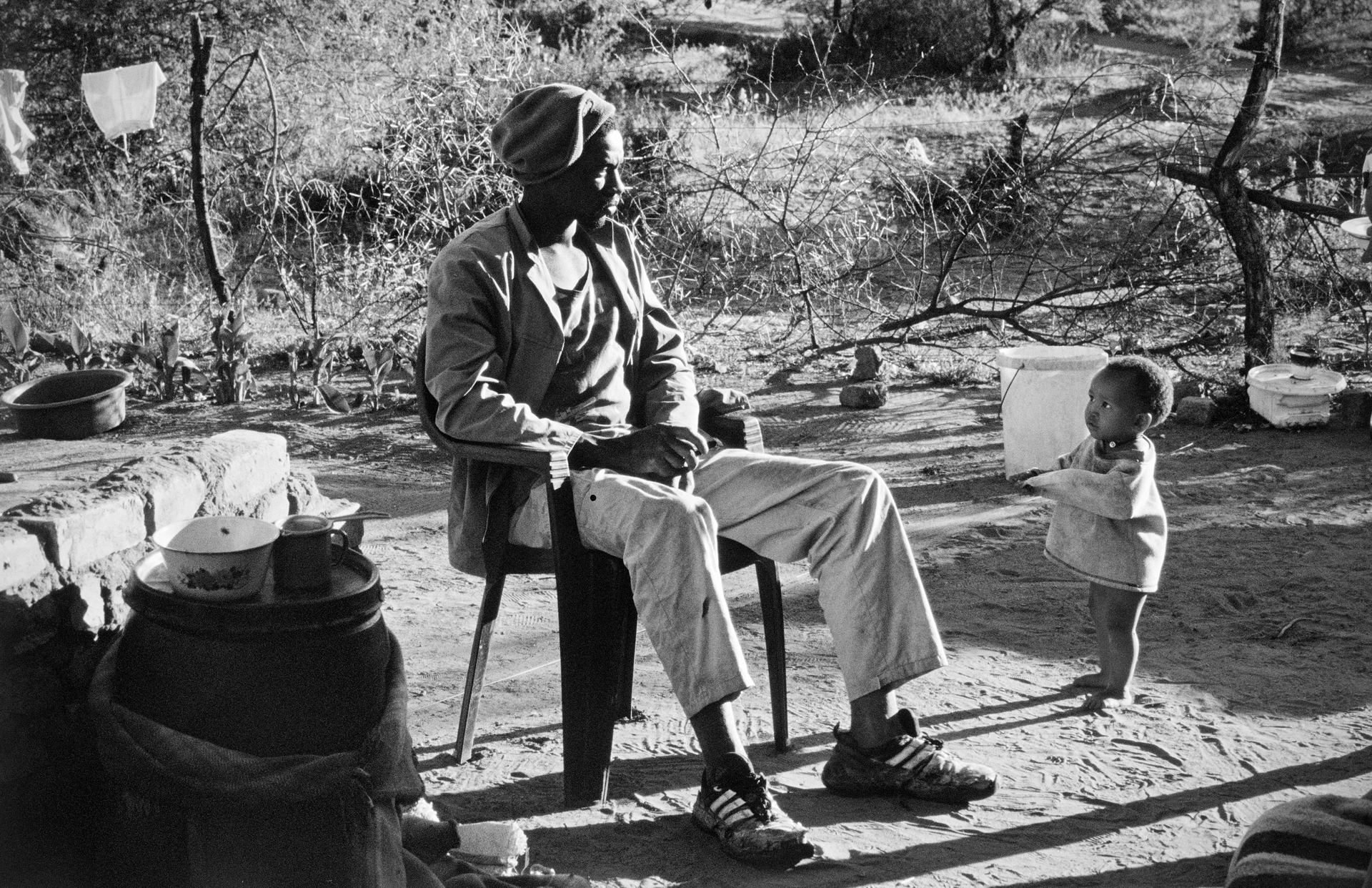

Town Bushmen. This family lives in a one-room concrete house on a dusty corner of the ghetto on Ghanzi’s outskirts. A local missionary, Beppie, brings the grandfather, Qace Qhomatca, sour milk. He has tuberculosis, and also AIDS - likely contracted years ago, when he was a community healer, through blood-letting practices. In the hot months the San live, squat, and sleep on the sand outside their houses, which are used mainly for storage. On August, 16, 2005, two months after this photograph was taken, Qace Qhomatca was buried. His anti-retroviral treatments came too late.