0%

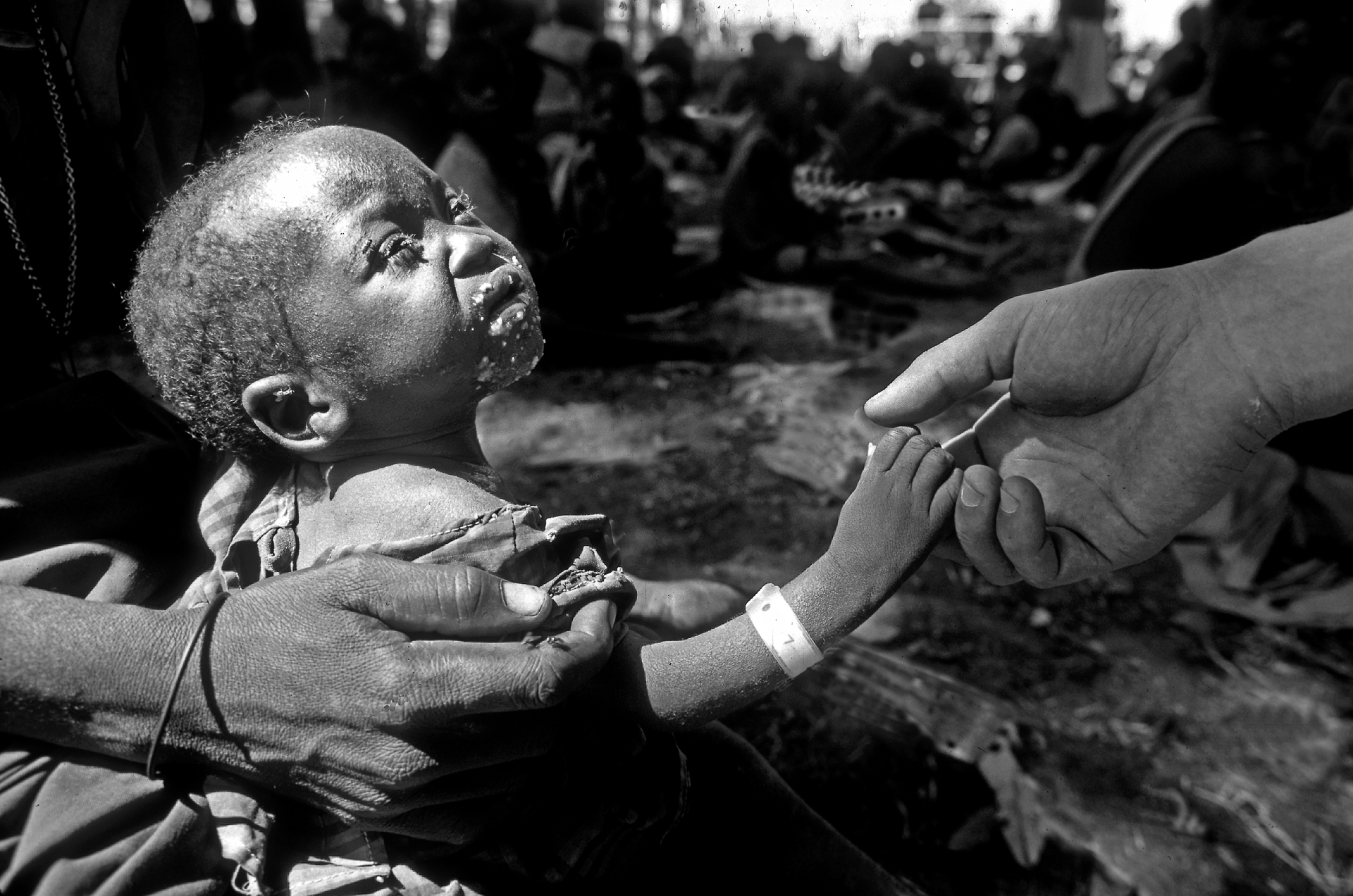

In the Spring of 1992, barbed wire surrounds a food storage area at a refugee camp near Baidoa, and Liboi on the Kenya/Somalia border where thousands of people are desperate for food. Hundreds die here everyday. Preventing people from rioting/ fighting over food, is a major security challenge when dispensing rations at this ICRC run camp. In a refugee camp in Kismayu, a withered young woman with two dying children told me she is afraid to accept food because “the people with guns come and kill us for it”. “We don’t work here, we do the we can,” says Peter Stocker, Head of the ICRC’s delegation in Somalia.

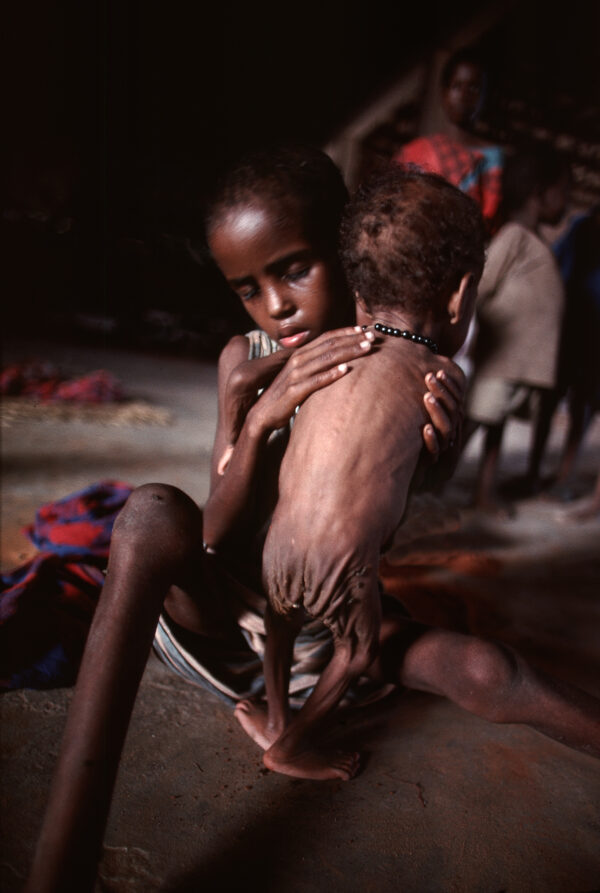

Children wait for food at an feeding station operated by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), in Kuito, a city of unknown population in the middle of Angola. Angolan's say that "what goes on in Kuito mirrors all of Angola." There is no electricity, no transportation, no running water, and no parents. If emergency food (supplied by the U.N's World Food Program and the ICRC), where cutoff, like war does everyday in Angola, or anywhere, then thousands of children will die within a week or two.

I was travelling through a tribal area called Wasiristan, the early 80's when I first went to Afghanistan while the Russian were still there.Here is a small village was a market of sorts. There were only very young boys here because all the womand and girls had been hidden away to avoid the foreigner, and all the older boys and men were away fighting Russians. Around the corner was this girl sitting alone agains a long mud wall.

I was travelling through a tribal area called Wasiristan, the early 80's when I first went to Afghanistan while the Russian were still there.Here is a small village was a market of sorts. There were only very young boys here because all the womand and girls had been hidden away to avoid the foreigner, and all the older boys and men were away fighting Russians. Around the corner was this girl sitting alone agains a long mud wall.

I came across this family camped along the Mekong River near the Vietnamese border. This is all they had, and their baby was but a few weeks old.

From where I sit the worst danger in the world is not “terrorism” or economic collapse, but apathy, and failure to see the big picture, which boils down to the fact that there is no us and them here, only us. We are all the world’s refugees. Today most refugees are victims fleeing dire abuse.

I think good photographs help us see ourselves in the subject, and they can change the way we see. Documentary photography for me is a means of telling a story. It involves paying attention, inside and out, and getting as close as I can. There is no magic to this. I spend a lot of time with the people who I photograph, and I often end up photographing my friends. Mostly the photographs I take are of ordinary people and events in everyday life. Some years ago I was stunned to learn that the total amount spend on “world health” was about 2% of what is spent on the military.

Young men in Gaza painting images of martyrs. It’s not surprizing to me that youth here glorify death when they have been humiliated by the Israeli Defence Forces for so many decades with the continued support of the American military and the hoards of Evangelistic Christian Zionists together with the Jewish Settlers, Benjamin Netanyahu and Donald Trump. The UN continues to condemn Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestinian lands.

Here are some latest (2020) statistics:

Number of Gaza Palestinians killed by Israeli snipers in past year: 304

Number of Gaza Palestinians injured by Israeli snipers in past year: 31,691

Number of Israelis killed by Gaza Palestinians in past year: 6

Number of Israelis injured by Gaza Palestinians in past year: 250

https://readersupportednews.org/opinion2/277-75/56422-focus-gaza-palestinians-and-israelis-wounded-past-year-by-the-numbers-31691-v-250

Members of the British based MAG (Mines Action Group) work on community education programs, and suppy much of the training and technology necessary to clear unexploded “bombies” in Xieng Khouang province, Laos, where hundreds of children continue to be wounded from "cluster bombs". Bombs that have remained lethal since the U.S Airforce dropped millions of them on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, - every eight minutes for nine years, - or two tons of bombs per person, - or $10 billion worth. Five to six-hundred tennis-balled size winged little spheres, were delivered in each of the millions of canisters dropped. Thirty-percent of them didn’t explode. They have been found in roads, trees, schools, homes, farm land, watering holes, irrigation trenches, and temples. An estimated 50,000 hectares of agricultural land in Xieng Khouang province is regarded as unusable because of bombies.

There is an explosion, very close. It comes from the furor in the middle of the road. Dr. Chris Giannou is the first to recognize the sharp crack and acrid smell of a detonated cordite grenade. When it explodes, we just happen to be only 50 meters away inside a Red Cross-flagged Landrover leaving the guarded gate to the headquarters of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in north Mogadishu, Somalia's war devastated capital city, in April, 1992. It's impossible to know exactly what is happening or might happen. Who and where are the perpetrators? Who are the victims? Who is injured and who is only bloody? In seconds, Chris identifies and loads three wounded into the back of the Red-Cross Landrover. Men from our two armed security escort vehicles follow his abrupt orders and load more of the wounded into their trucks. In a convoy we speed out of Mogadishu towards Kasani Hospital, seven kilometers away. The boy stares in bewilderment at his dangling, ripped foot, at the place where his ankle used to be. Holes puncture both legs, and a piece of flesh is missing from one arm. There are no tears in his eyes, only disbelief.Fifteen people are injured and one is dead. We learn later that children were playing with a grenade.

Mogadishu Somalia 1992. Three young armed “militamen” scrutinize me and my cameras. Mostly I would avoid contact with armed bands of youth roaming the streets of Mogadishu, but sometimes intuition told me that these boys where more curious than suspicious of me, and would be happy to pose and show off for my camera. For the moment, I was not their enemy. I took the picture quickly and moved on before anything changed, as it can so quickly here. And when I asked a man I met on the street, what these young “militiamen” might think of me walking the streets of Mogadishu, he replied that “they probably think that you have armed security people guarding you from the surrounding roof tops”.

Decades of war in Mozambique have left the streets of its capital city, Maputo, plagued with orphaned children who survive on the city’s garbage, in destroyed and looted buildings, and by trolling the streets for anything of value. They are all malnourished, diseased, and often traumatized by things too horrible to imagine, like the twelve-year-old boy who told me how Renamo’s rebels had forced him to shoot both his parents. Many of these youth were “child soldiers”, and now that the actual “shooting” war is over, another kind of war has begun. These children have nothing to do, and no where to go. They are war babies with often dangerous skills, and I wonder what kind of parents and leaders they will grow into.

Orthopaedic Centre, Wazir Hospital, Kabul, Afghanistan, 1996. Wazir Hammond, age nine, requires prosthesis refittings every six months. He rests against a wall of sandbags that protect the hospital against rockets, shelling, and bombs. An estimated 10 million landmines pollute nearly 500 square kilometres of land in Afghanistan, where one out of every five children born dies before age five. 100,000 more will perish, from hunger and cold, largely as a result of the recent bombing of Afghanistan.

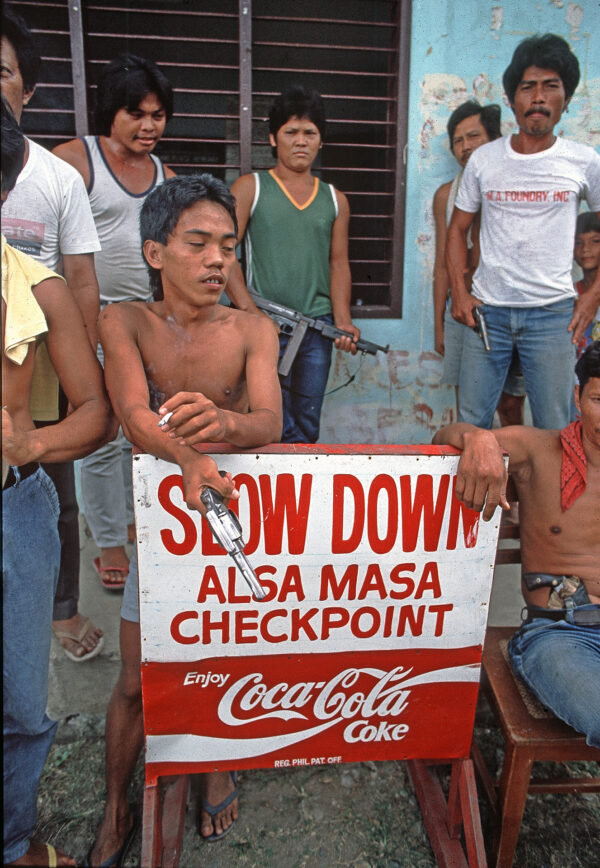

Davoa City in the southern Philippines, Mindanao, child members of the anti-communist Alsa Masa paramilitary forces line up in front of a movie theatre carrying real M-16 automatic weapons and wearing Rambo hats, to watch a "Rambo" film. One night I watch them at a roadblock in the middle of night, stopping cars to determine who is a communist and who is not. They kick a severed head around on the road. Indescribable violence is regularly inflicted on anyone who disagrees with these children, who vehemently believe that God and democracy are on their side. I covered this story in the early 80’s. But little has changed here since then. Fundamentalists still reign here today.

Quito, Angola, three decades of war continues, 1995, the front line is the main street. Jonas Savimbi's rebels and President de Santos' government troops are facing each other from behind the shelled and shot-out remains of buildings on either side of a thin "no-man's land." A few blocks away children play war games...they mimic the adults in great chilling detail.

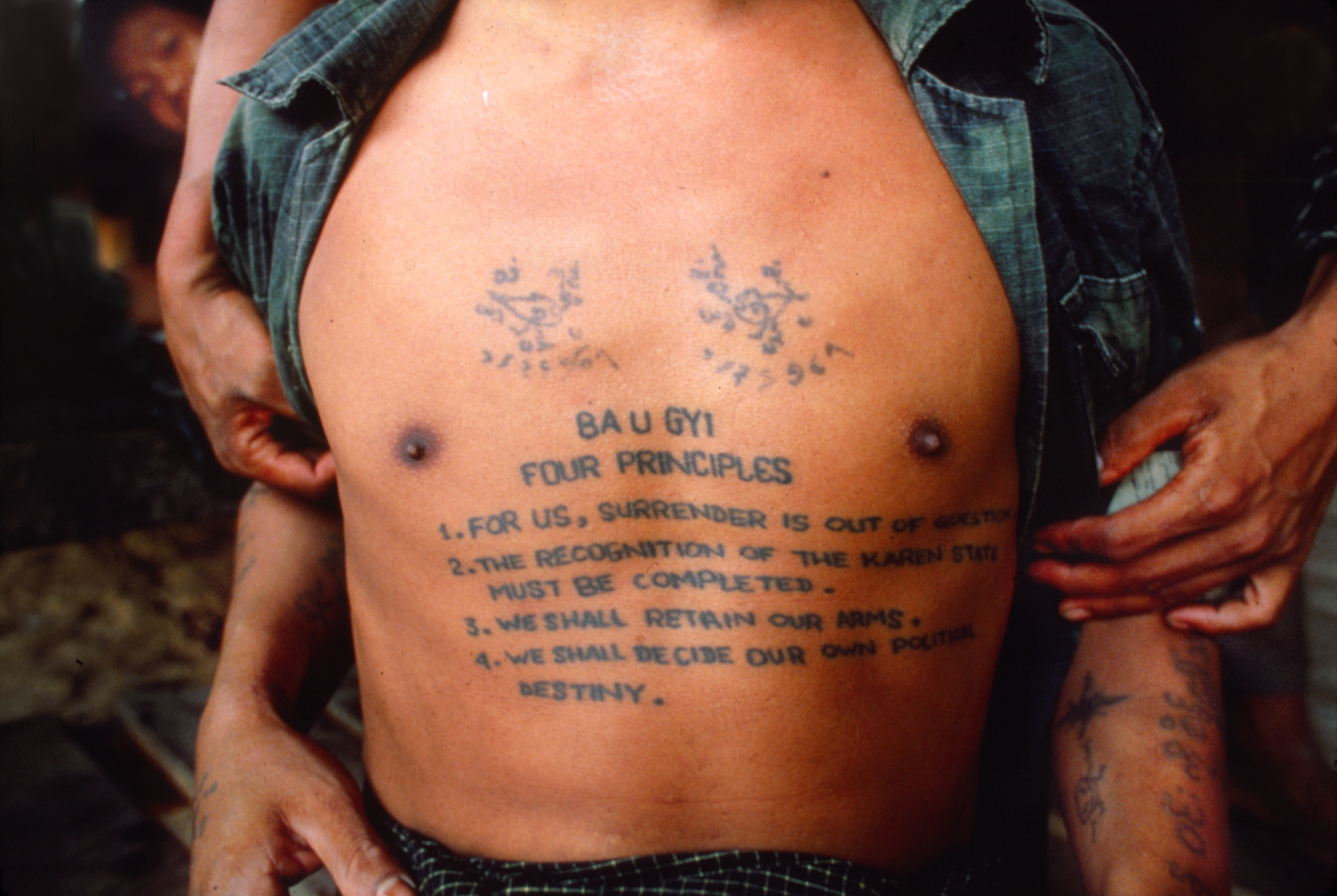

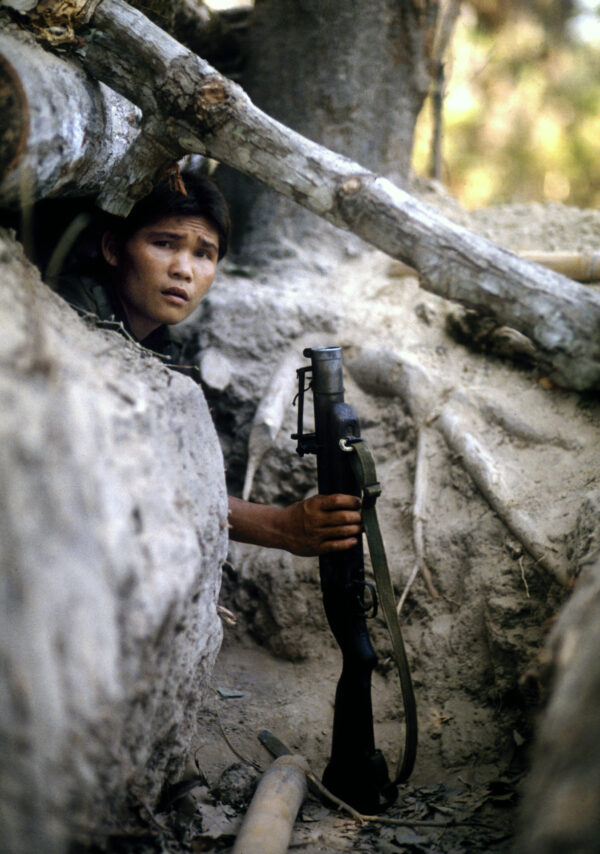

A young soldier rests in the barracks at Mannerplaw, Burma, the fortified headquarters, training ground, and last major stronghold of the Karen National Liberation Army. The camp is on the Burma side of the Salween River 200 km. upstream from the Thai bordertown of Mae Sot, a 12 hour bus ride from Bangkok. But in another world.

Hw displays a tattooed chest that spells out his fight for freedom and democracy against an undisputedly suppressive Burmese Government. These young soldiers appeared to me only slightly like children with guns. They had young bodies, but old faces. A cigar-smoking fourteen-year-old, with a AK-47 over his knee, tells me how he killed ten Burmese soldiers the day before with claymore landmines.

The top of Pagoda Hill is a boat and truck ride and two days walk from Manerplaw, and light years away from everything sane. I am soaking wet with perspiration and aching from exhaustion after hours of climbing to the top this forsaken patch of high hill top, -on the edge of a maze of trenches dug in dusty pulverized earth. The few trees that remain are shredded, splintered and scarred from bullets and shell fragments. The putrid unmistakable smell of rotting flesh hits my nostrils and churns my stomach. I vomit the rice and fish paste I had eaten 5 hours earlier and kick powdered dry trench dirt over it. I wondered whether I will eat again. Steven, an English-speaking medical officer and my front-line guide explaims that 29 Burmese were killed here yesterday trying to charge up the hill. They were mostly killed by claymore mines planted along the side of the hill, that are fired remotely through wires leading from our hill-top trenches. Steven explains how they effectively cut the Burmese soldiers in half. Steven popped his head up. In an instant the silence was cracked by a hail of machine gun fire that raked the dry dirt and shredded trees behind us. "You smell that gun powder?" Steven asked, "There is a Burmese soldier maybe 10 meters in front of us. He is very close. I think they sent him close because they know there is a foreigner here. They hear us speak English." Steven lifts his Kalashnakov machine gun above his head and sweeps a barrage of fire in front of the trench. The acrid smell of gunpowder momentarily displaces the stench of rotting flesh rising up the hill. When we hear the distant thunder of artillery, and the screeching whistle of incoming shells; everyone sinks very low in the trenches. The percussion and excruciatingly loud explosion shakes the earth, and my insides, and jolts my body off the bottom of the trench, where I am, face down, with my hands over my ears and head. Dust is driven into my nostrils. I’m suffocating, frozen, and mortified, with no place to go. Sweat runs off the faces of the two boys, 17 and 20 years old, who crouch in the front trench with us. After each shell hits they strain their eyes to see through the dust, and over the logs piled in front of the trench to prevent grenades from rolling inside of it, and shoot blindly down the hill, where the Burmese soldiers are. In the midst of chaos and paralyzing panic comes silent times between artillery barrages and machine-gun fire. My thoughts and heartbeat seem surprizingly loud. Over the next three days I find myself believing that the secret to my survival here is because of the hat Steven had given me to cover up my bald head. Three men had been killed and 9 injured this morning.It is so crazy here, that my hat is keeping me alive. This morning five Karens had been killed and nine injured, and below the hill lay some 29 dead Burmese soldiers.

Children in Gaza play a game called "Arabs and Jews". They take sides and play out the roles, often in staggering detail, including some pretending they are parents screaming over dead children. Psychiatrist Dr. Eyad Sarraj calls it Post Traumatic Play Syndrome. All these young people have witnessed horrible, unspeakable things