Trauma in Gaza

Multitudes of cheering Palestinians shake hands, kiss, hug, and cry with each other on the streets of Gaza City tonight. Car horns blare and people jubilantly shoot their guns into the air to welcome their brothers from the Palestinian Liberation Army, and watch the last Israeli soldiers leave. After 27 years of Israeli occupation, Palestinians fly their flags from every rooftop, and Yasser-Arafat-pictures across every street, without fear of being beat, shot or imprisoned. For many Palestinians, it is their first experience without draconian curfews, Israeli patrols, barricaded roads, barbed wire, search lights, watch towers, house searches and demolitions. For the first time since 1967, Gazans are free to touch the sand and swim in the warm moonlit water of the Mediterranean Sea. And tomorrow, Palestinian children will have no Israeli soldiers to throw stones at.

“Sarwarna, Sarwarna,” “take my picture, take my picture,” children yell as they swarm around me, pushing and shoving each other for position in front of my camera lens. They wave their hands and make victory signs with their fingers, and pose with toy guns. Some Palestinian children hang mementos around their necks; the Israeli bullets that shot them only a few months before. Very small children, between 3 and 7 years old, daringly slap my body then run away, and from a distance, defiantly hurl stones at me. They assume that all foreigners are Jewish, and tauntingly test me by calling out “Shalom” – the Hebrew word for “peace.” These are the real “Children of the Stone,” the ones who learned from the Palestinian “Davids'” and the Israeli “Goliaths,” during the “Intifada,” or uprising.

The smell of rotting garbage shrouds the hot humid air. Sewage drains down troughs along narrow alleys with high walls that separate a maze of crowded cinder-block houses. Kamal, a young Palestinian boy, stands beside the first iron door on the left. He lives here with his parents and six brothers and sisters in the Beach Camp, one of seven Palestinian Refugee Camps inside the Gaza Strip. About 40% of Gaza’s 350 square kilometer area remains occupied by an estimated 9000 Israeli soldiers who guard the Israeli border and 4500 Jewish settlers. Nearly 900,000 Palestinians live on what is left. It is one of the most densely populated places on earth. Over fifty-percent of the adult population is unemployed, and more than half the population is under 16 years old, and almost all of them defied the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

“My 14 year-old cousin was shot and killed for throwing stones. I threw stones at the Israeli soldiers, but escaped and ran away,” says Kamal. Once they chased me home. My mother tried to protect me, but they pushed her into the wall and took me to their jeep. They punched me and beat my head with the back of their guns and one of them held his cigarette on my fingers and legs. Another soldier cut my hand with his knife. They took me to an administration building. My head and hand were bleeding. They said “IF YOU DON’T STOP CRYING AND TELL US WHO ORDERED YOU TO THROW STONES, WE WILL SHOOT YOU. WE HAVE KILLED BOYS YOUR AGE BEFORE AND WE WILL KILL YOU RIGHT HERE.” I said that my friend Amjad told me to throw stones, and I showed them where he lived. On the way, the soldiers swore and tried to make me drink from a small bottle. I think maybe it was alcohol. I refused. At Amjad’s house they saw that he was 8 years old, like me. I cannot forget what they did to me,” he says. His voice is soft, almost inaudible.

Amjad and Kamal remember throwing stones at the Israeli soldiers almost everyday. “We would wait for jeeps along the beach road, and sometimes we would go looking for soldiers, says Amjad. What happened when the soldiers brought Kamal to your house, I ask Amjad? “My father had to show the soldiers his identification card to prove to them that I was Amjad and 8 years old. They punched me in the face and kicked me. My father tried to protect me and they punched him. My mother cried, “don’t kill the child,” and when she tried to help me, the soldiers hit her. My father begged the soldiers to let him beat me. They told him to use a stick or else they would arrest me. My father had no money to pay the Israeli’s to get me back from their prison. Before the soldiers left, they exploded a noise bomb by our door…I’m happy the Israeli soldiers are gone, but I miss them,” says Amjad boldly, as if they were a source of strength for him. – and they probably were. While all children are victims, some are passive and others are pupils of war.

“Trauma” researchers at the Gaza Community Mental Health Program suggest that “Palestinian youth in despair are prepared to sacrifice everything and themselves for their liberation…Death is conquered by glorifying the life thereafter. Children who threw stones have fewer symptoms of trauma because helplessness was replaced by assertiveness..their tension found a legitimate target for their anger – the Israeli soldiers.” Psychiatrists found that exposure to traumatic experiences in South Africa “increase a child’s capacity for moral reasoning, which is associated with cognitive development.” However Dr. Eyad el-Sarraj, the Director of the Gaza Community Mental Health Program (GCMHP) points out, “children who throw stones are not made of stone. They suffer like any human being facing overwhelming violence and loss.”

Trauma is “any external event, outside the range of usual human experience, that is intense, sudden, and that overwhelms almost anyone’s psychological capacity to cope.” Traumatized people seek never to have the experience or sensation again. Research conducted by the “Gaza Community Mental Health Program” on 2779 Palestinian children with an average age of 11 years old found that 69% of them were exposed to more than four different types of trauma and: 93% had been tear gassed, 85% had their homes raided, 55% had witnessed the beating of their fathers 42% had been beaten, 31% had been shot. 28% had a brother imprisoned, 19% had been detained, 3% had suffered death in their family, and 1.1% had their homes demolished. Dr. Eyad el-Sarraj, a psychiatrist, who founded and directs Gaza’s only mental health program, and who was also a former Palestinian Peace Negotiator, says that ” witnessing their homes demolished, or their fathers’ being beaten are the most devastating traumatic events children experience, next to being tortured.

Kamal had many symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: aggressive behavior, isolation, disobedience, sleep disturbances and nightmares, fears (soldiers and darkness), nervousness, emotional detachment from friends, increased emotional attachment to his parents, avoidance behavior, depression, apathy, difficulty in concentrating over school work, and bedwetting. “He needed psycho-therapy for almost a year,” says Raghda Saba, a psychologist who uses play therapy at the Gaza Community Mental Health Program.

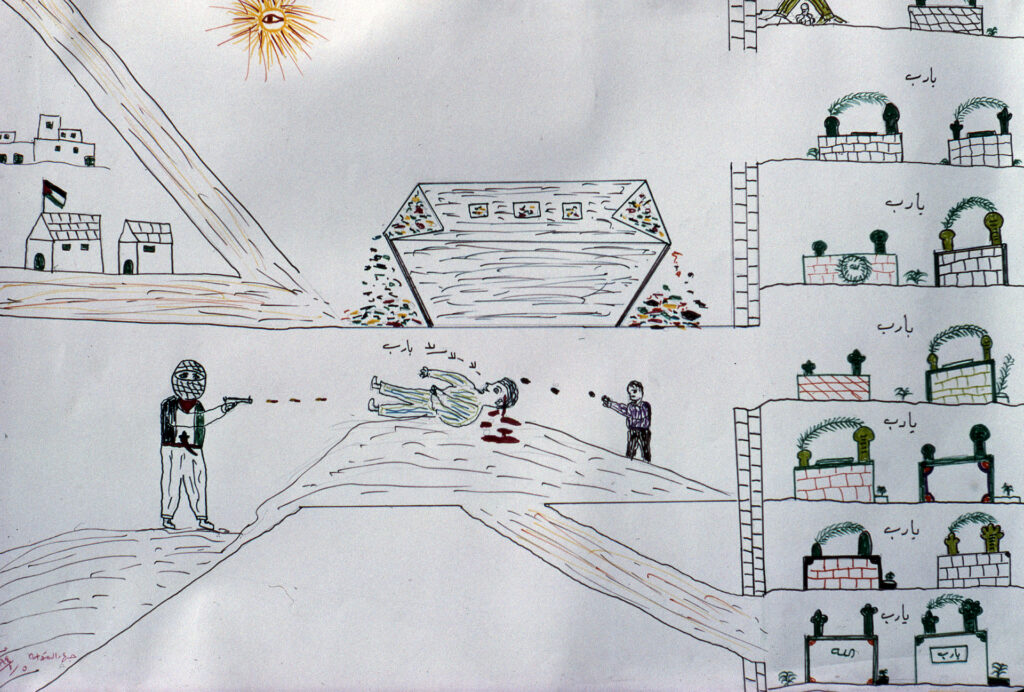

Play is the work of children, and in the “play room,” Kamal was safe because his trauma belonged to the house, the masked men, the soldiers, the jeep, or the dolls. Rahgda tells stories and jokes about the child’s interpretation of the toys or visual language. Trauma is often perceived as mental images, and in the playroom they are metaphorically played out. Toys, like drawings and storytelling allow children to express their rage, both as a fantasy and internally. Their drawings and the toys they chose are clues to integrating their disassociated traumatic experience into the rest of life. Through observing and interacting with Kamal at play, Rahgda helped him gain some control over the fragmented feeling associated with his images and memories of what the soldiers did to him. He learned to detach himself from his symptoms, his repetitive compulsions to beat his younger brothers and sisters for example, without having to talk directly about himself. Kamal needed therapy to reclaim his autonomy; to know that his feelings of helplessness were not forever, and that he was not alone in his pain.

At home Kamal had a graph on his wall that charted his good and bad behavior, and he could “erase” the “black marks” by doing something good. With a combination of play therapy and simple behavior modification, and supportive parents, Kamal mastered his trauma. “For several months he was doing fine, until the day after the Washington Peace Accord was signed, when he went outside and found Israeli soldiers still present,” says Raghda. Kamal returned to Raghda to help him understand why the soldiers didn’t leave overnight. Kamal is only one of 3,000 children treated for “PTSD” since the Gaza Community Mental Health Program opened four years ago.

“At least 60,000 traumatized children in Gaza require immediate psychiatric therapy. Everybody in Gaza is traumatized… I remember a psychiatrist who came to Gaza from the United States and after a week here he became traumatized…he wanted to kill Israeli soldiers…we had to physically keep him from doing that, for us it has been like living in a prison for 27 years,” says Dr. el-Sarraj. He describes the last 7 of the 27 years of occupation, the “Intifada” or “shaking off” years, as “like living through an earthquake everyday. Every aspect of everyone’s life was controlled by calculated mass suppression which inevitably leads to frustration and violence.”

“Over 27 years the Israeli Government institutionalized humiliation and collective punishment under the pretext of security….They occupied Gaza and they made a profit doing it,” says Marzen Shagura of the Gaza Center for Rights and Law, an Affiliate of the International Commission of Jurists – Geneva. He explains how Gaza is economically dependent on Israel. How the Israeli Government undercut Gaza’s citrus fruit export prices, and restricted what Palestinians could grow and import. “Through military orders, taxes, fines, and intimidation, they created apartheid here,” he says, in reference to the thousands of Palestinians who wait in lines at the “slave market” every morning at Erez Checkpoint, the main border crossing between Israel and Gaza, to be “permitted” to work in Israel. Thousands of Palestinian houses were sealed or demolished by anti-tank missiles or bulldozers, after families were often afforded only minutes to vacate them. Using “catch 22” legal tactics, involving combinations of British, Jordanian, Egyptian and Israeli law, land was confiscated. Gardens and crops were massively destroyed and trees uprooted by the thousands, food supplies destroyed, and water tanks shot full of holes and urinated in. Children, fathered by Gazans but born to mothers not originally from Gaza, have no legal status. Family reunification was not a given right under Israeli occupation, and mass deportations and administrative detentions were ordered without charge or trial. More than 400,000 Palestinians were imprisoned and most, (according to Amnesty International, the Red Cross, and numerous other Human Rights organizations – including Israeli ones) were tortured. “Israel controlled everything including, access to medical facilities, water, electricity, telephones, and even some radio frequencies. Gaza is like a test tube for Military Orders,” he says.

“The Israeli Government controlled Gaza with over 1300 military orders. They did whatever they wanted and then they sanitized their operations under the pretext of military law and security. They are paranoid and obsessed with security. It is their biggest export, says Mark Taylor, a former Canadian journalist and information officer for The United Nations Refugee Works Agency in Gaza. “It was law by rule, not rule by law. It wasn’t that the Israeli’s had a policy to kill children, but rather the fact that their military orders allowed them to kill children. Demonstrations became clashes only because of the presence of Israeli soldiers. In a 1000-page report detailing violence perpetrated on children by Israeli occupation, Swedish Save the Children concludes that: “a composite picture of the average child killed by gunfire shows a 12-year-old boy who was not participating in stone throwing when a soldier shot him in the face, – 20% suffered multiple gunshot wounds, and 12% were shot from behind.” According to Professor Jim Graff of the University of Toronto, a seasoned visitor to Gaza and author of “Palestinian Children and Israeli State Violence,” and the Director of the Near East Cultural Center in Canada, “more than 5000 Palestinian children under the age of 15 years where shot by Israeli soldiers, and more than 1000 children were less than five years old….They took deliberate aim at children,” he says.

The plight of Palestinians brought Dr. Eyad el-Sarraj to dedicate his life to healing their pain. Like many Palestinians, he recognizes education as the most sustainable weapon against oppression. When he was five years old his family was forced out of their home in Beir Sheva when the United Nations declared their land part of the new State of Israel. Palestinians rejected the “partition” because there were more of them than the Jews, yet they were offered less than half the land. His family fled to Gaza, which was under Egyptian control, and from there he witnessed two more decades of Palestinian dismemberment including, the Suez War in 1956, the October War in 1973, and the Invasion of Lebanon in 1982. The biggest blow however came in 1967, when Israel started and won the Six Day War with Egypt and occupied the West Bank, the Egyptian Sinai Desert, Syria’s Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip and then annexed East Jerusalem – all in violation of International Law and the 4th Geneva Convention. “I knew if I was to become a doctor, it would be a way to help, and not kill anyone,” he says one early morning while we walk along the Mediterranean beach. “I started to smoke in medical school in Alexandria because someone told me it covered up the smell of formaldehyde on the cadavers…I hated memorizing body parts, so I decided to study psychiatry at London University…If it wasn’t for this sea, and my garden, I couldn’t stay here,” he says, as we watch a Bedouin family wash their sheep in the sea.

“I had an orange grove. I am now in a refugee camp. What do I tell my children?” says 73-year-old Raja el-Sarraj, Dr. el-Sarraj’s father. After Israel occupied Gaza, I took my wife to see my old house. Do you think the people will forget this? They will never forget this. I say to my sons, and they say it to their sons. They will never forget where our home was. The Jews took everything. I fled away, with my children and wife, without even my trousers. I left everything there, in Bier Sheva,” he says.

“Violence has to end with the victim, in the same way as the peace process interrupted so many years of violence,” says Dr. Hanan Ashrawi, aformer Palestinian peace negotiator and a member of The Palestinians for Citizens’ Right’s Commission. ” The Jews went through the horror of the Holocaust and it affected everyone. They wanted us to take responsibility for their pain. The Palestinian pain needed to be legitimized. It has to do with the way we deal with authority. When we reclaim our basis of authority; then we can deal with trauma in objective conditions. We have to have playgrounds and institutions that support creativity and self-expression, and establish social systems that do this. That is the only way we are going to deal with hundred’s of thousands of traumatized children.”

Walking through Jabalia Camp, where 70,000 people live in .6 of a square mile; I watch children ranging in age from 4 to 17 years old play a game called “Arabs and Jews”. The little ones play the “Arabs” who throw stones and rotten fruit, while the bigger ones play the “Jews” who carry homemade replicas of M-16 machine guns. Why are you playing this game, I ask a boy wearing a red shirt? “We have nothing else to do….I want the Israeli soldiers to come back so we can show them the real Intifada,” he says, while raising his pants and showing me scars from two Israeli bullet holes in each of his legs. He is sweating and eager to begin another game. The little boys gather together and chant, and as the “soldiers” approach, the “Arabs” drop to the ground in mock Moslem prayer. The “soldiers” laugh, and prod them with their gun barrels. Suddenly the young boys jump up, run a short distance, then turn and hurl their “stones” at the older boys. Dust flies from cans of sand heaved as make-believe tear-gas canisters. Some “Arabs” are shot and fall, thrashing dramatically to the ground, while others lay motionless. The captured and wounded are punched, kicked and dragged across the ground. Guns are pointed at their heads. Some children play Arab women and rush into the clash to protect their children, and when all the “Arabs” are subdued, another game begins. They play “funeral procession” where Arab mourners are beaten and shot by the “Jews,” and “Hebron Massacre,” and “Mohammad Ayyad” the collaborator. There is real aggression and tears and I wonder why a child walks in a large circle repeating what he heard coming from loudspeakers on Israeli jeep patrols, “People of Jabalia, you are under curfew. Anyone found outside their homes, looking out windows, or standing on their balconies will be shot…People of Jabalia, you are under…”

During the intifada, curfew was every night and often 24 hours a day for weeks – one lasted 42 days during the Gulf War. Curfews paralyzed and kept everyone from attending jobs, schools and their medical needs for 3473 cumulative days since 1987. In Jabalia a father says, “We didn’t have enough food…I had to sit by the door to prevent my children from going outside, like a prison guard. ” Research by Dr. el-Sarraj and psychologist Samir Quta shows that family violence, fear, anger, aggression, disobedience, withdrawal, worry, frustration, and depression are among the “various behavioral and neurotic symptoms children exhibit during curfews.” Aimed at breaking Palestinian resistance, collective punishment was rampant in Gaza. According to UNICEF, schools, playgrounds, and sports clubs in Gaza were closed by “Israeli Military Orders” for nearly as much time as they were allowed to be open. While the Israeli Government viewed schools as hotbeds of revolution, the Israeli Section of the Defense of Children International told the Israeli Parliament, the Knesset, that just the opposite was true. They said that “besides having an especially devastating effect on young children, who don’t have the basic reading, writing and arithmetic skills, children tended to play on the street – where the soldiers were, and they learned confrontation, and how to resist authority and admire guns.”

What psychiatrist’s call reenactment, or “post traumatic play,” is endemic in Gaza. It has to do with the imperative to master trauma in order to legitimize it. “You need repetition to master the trauma, that is why torture victims often identify with their torturers,” says Dr. Fredrico Alloidi, a visiting psychiatrist from the University of Toronto and an expert on the psychological effects of torture. It is also why victims become perpetrators. At the beginning of the intifada the Israeli Military authorities were criticized publicly in the Israeli Parliament, the Knesset, for suggesting that Palestinian workers in Israel should wear special armbands – pointing out that it was too reminiscent of the “Star of David” patches that the Nazi’s forced Jews to wear in Germany. During the Intifada, an Israeli soldier had the following to say in his letter to the editor of the Hebrew-language newspaper “Koteret Rashit:” “Beatings have become routine, but here, of all places my awareness suddenly begins to stir. It says: “A child is a child”…in spite of the fact that he is instigating war and in spite of the fact that he’s a little “whore.” He’s a child. My awareness of destruction, the fruit of a humanistic education of many years standing, comes to his defense. It encircles the child and tries, with all its might, to preserve itself. But I’m a soldier, I’m obedient. I raise the club… I learnt the terminology: there are halting blows, direct blows, and fracturing blows–all of which fall under the category of “reasonable blows”. After painstaking training, I achieved the required expertise needed (to deliver) the blow that breaks everything: the club is raised in a circular motion. For the proper impact, two-thirds a length’s distance is required, which is reasonable force…I beat my awareness to a pulp. When my consciousness is crushed and I find myself an animal and not a human being, recalling what happened to the Jews 45 years ago, I stand there in my uniform and my metal helmet, with a gun and a club – but no consciousness…”

“The soldiers thought nothing of coming into schools, even kindergartens,” says Mostafa, a teacher at Alkarmel High School in Gaza City. “They beat and humiliated students and teachers, vandalized, defecated on floors, and threw tear gas canisters through windows. The 29-year-old teacher refuses to give me his last name, and when I ask why, he says, “what if the Israeli soldiers come back here? And even if they don’t, there are Israeli spy’s in every country….This morning when you first arrived at this school, the headmaster thought you were a Jewish spy…The Israeil’s made us suspicious of even our own brothers…This is the first time in 7 years that the teachers are not afraid of the students… A teacher was shot by masked students in front of his class, because they suspected him of being a collaborator,” Mostafa says.

What do you want to do when you grow up? I ask 7-year-old Abdul. “I want to get a gun and kill the neighbors,”he says. His father, Jahad, stares with glazed eyes. Life for his family stopped 18 months ago, when he found Nedal, his 16-year-old son, on a garbage pile with a bullet hole through his brain. He was executed by the Ayman, the son-in-law of the family who lives next door. They say Nadal was collaborating with the Israelis. His friends say he was a loyal Palestinian who was shot twice and imprisoned 13 three times by the Israeli’s. Nadal belonged to the moderate “Fatah” faction of the PLO. He wasn’t a “Fatah Hawk” or an organizer, or leader. The neighbor’s video entertainment store, (like movie theaters and playing music – which ceased during the Intifada) was considered shameful. And when the neighbors refused to close their store; it was burned to the ground. Jihad believes the neighbors think that Nidal torched their store and they killed him for revenge, and conveniently cursed the family with “collaborator.”

“Violence is normal in Gaza,” says Samir Zaqout, a Social Worker for the Gaza Community Mental Health Program. He visits Jahad’s family regularly, and understands trauma. “The soldiers broke into my house more than 70 times during the Intifada,” he says. “I was beat up, tortured for 13 days, and imprisoned for a year because I was a school teacher and a Palestinian nationalist.

“Four days ago the neighbors shot three holes through our door,” says Jahad. “I’m not crazy, but if I had a gun, I would kill them right now, and if I don’t do it I hope my son will,” he says. His eyes seem frozen, yet unable to hold back tears that seep from the gaunt sockets, blackened from sleepless nights. His wife sits across the room, motionless, trying to understand a story with no end, and her son sits quietly next to her. The room is a shrine to Nedal. Pictures, posters, letters, a large Palestinian flag, political slogans, and testimonials from Fatah supporters, decorate the walls. “I cannot believe what has become of my life, how it was before and how it is now… I have become a zero man,” Jihad says. “I think you will have to leave this house,” says Samir. “It is like living next door to the devil.”

“I saw a man the other day who couldn’t stop crying. He was frozen in mourning,” says Dr. Sama Hussan, a Palestinian/Canadian and a visiting 14 psychiatrist from Toronto. He gives seminars on “Family Therapy” at the Gaza Community Mental Health Program and one day I go with him to visit a family of eight in Khan Younis. Soldiers broke into there more than 100 times. Everyone in the family was shot and beaten. Three sons were imprisoned, and the father, now disabled, leans on his cane and lethargically stares at the floor. The eldest son assumes authority, even though, according to Dr. Hussan, his older sisters are more qualified for the role, but authority in a Moslem family has definite rules. “You have a family of heroes,” says Dr. Hussan to the mother. “No I have nothing,” the people in Tunis have won everything, she says, her face strained and hardened with tearless pain.

I found the contorted face of trauma everywhere I went in Gaza. “How can you take care of me, when you can’t take care of yourself” says a 12-yearold boy to his quadrapalegic father, who lies on the floor of their home in Khan Younis. Two years ago soldiers beat him in front of his family, because he refused to put out a burning tire with his bare hands. Another son runs around the room pointing and shooting a toy gun. He reminds me of the young children that insist on training every morning with the Palestinian Military recruits – the ones who hope to join the “intelligence” branch of the army, or police – the real authority.

In another house in Gaza City I meet Alam Akram, a 15-year-old boy, who became a paraplegic 18 months ago when an Israeli bullet shattered his neck. His father, once a prosperous businessman, says to him: “You have ruined my life, your mothers, and all your brothers’ and sisters’ lives…but don’t worry (as he cradles his son’s head in his hands), in two years there will be a surgical operation to make you better.” Samir, the social worker, listens patiently to him. “My business is gone, all our savings are gone, the 15 car, my wife’s jewellery…everything is gone and the hospitals and the relief agencies neglect us…The rich countries should pay to renovate my house, buy a car, and pay for a nurse for my son, so I can go back to work…I have to turn him over three times every night,” the father says. His tragic dance of denial ends abruptly when a Palestinian soldier struts into the room, walks over to Alam’s bed, holds the chamber of his Kalashnakov close to the boys head, and fires the gun out the open window in a salute to the boy. No one, except me, flinches from the loud percussion, and Alam smiles with admiration and proud acknowledgement.

As we leave their home I ask Samir what he can do for this family. “They have to call me. If I initiate the next visit the father will want money from me, and when I refuse he will add me and the “Program” onto his list of people to blame…He believes money will solve all their problems…He keeps his whole family stuck in denial…He is so fearful he cannot move,” says Samir.

Symptoms of trauma are defense mechanisms against unbearable circumstances and events. They are also signs that the mind is healthy. The problems start after the circumstances are over, but the defense mechanisms remain, and keep victims stuck – sometimes for generations.

For Jewish settlers, especially the Messianic ones, the omnipotent Zionists – the expansionists, and “God’s Chosen People;” peace means giving up their dream of the Holy Land – a complete Eretz-Israel, while for the ‘Hamas,’ the Moslem fundamentalist party; peace means betraying the dead whose martyred blood stains the land they lost. With unhealed wounds, both extremes blindly fight to correct past injustices, and every disappointment in the peace process elevates their righteousness. By reacting with anger and aggressiveness, they deny their guilt feelings. Psychiatrists call this “egotism 16 of victimization.” For them it is simpler to have answers than to wrestle with questions of conscience, or confront their weaknesses and fears. Everybody wants peace – but under what terms? Neither Zionist nor fundamentalist can see relinquishing land, or empathizing even a little with the other side, because compromising is tantamount to annihilation and betrayal. Haunted by the holocaust and victimized by Zionism, it is not surprising that the collective memory of Israel is paranoid and obsessed with security, or that the Israeli Government, especially the Labour Party, resisted the peace process for so long by condemning moderate Palestinians as incompetent, and encouraging Hamas – who foment Palestinians to fight among themselves, while saying “Lets kill all the Jews.”

Dr. el-Sarraj knows that trauma infects deeply and healing it has only just begun. Much of his time is spent involved in the larger political arena, attending conferences, and raising money for the “program.” He plans to expand the Gaza Community Mental Health Program to include an education and training center for mental health practitioners. “The danger now is that Palestinians will turn their anger on each other. I suspect we will see an increase in family violence…In the Palestinian Police force many have been tortured, and now that they are in positions of authority, maybe they will start to abuse those around them,” he says. “And for the Israeli’s, they must know that Zionism isn’t working, because it created for them another victim and another enemy.

On the road past Netsarien, the Jewish settlement nearest Gaza City, I’m stopped at each one of three Israeli security checkpoints. One soldier trains his machine gun at the car from his concrete reinforced watchtower, two others stand behind the car, and a fourth approaches the car window. “Are you Jewish,” an English-speaking soldier asks? “No, I’m Canadian,” I reply. “And where are you are from, I ask?” “Holland,” he says. “And why are you 17 here,” I ask? “Because I am Jewish, he says belligerently. According to Israel’s “Law of Return,” anyone born to a Jewish mother can claim citizenship in Israel. “Where are you going,” he asks? “To visit Gosh Katif,” I say.

Gosh Katif is the largest Jewish settlement in the Gaza Strip. Heat waves blur the thirsty desert, contradicting the green grass, flowerbeds and suburban looking houses inside the guarded gate, along the boulevard leading to the stylish administration center. Across the road is a modern school, surrounded with barbed wire and next to it is a shopping mall. Two well-dressed women stroll by pushing two baby carriages, and a man sits under an umbrella at a sidewalk cafe reading a newspaper. His Uzi Machine gun on the table. I stop to buy a drink and am served by an older man with a Brooklyn accent. His name is Israel Lillithal, and he came here from New York City 8 years ago, “for the cause,” he tells me. I ask him what he thinks of the Peace Agreement? “Rabin has made a big mistake, why should we give the Palestinians our land when they have all those Arab countries they could go to,” he says. “We give them electricity and water and money. They are the like Svatz (Blacks), in New York City, always complaining,” he says dauntlessly. And what do you think when human rights groups, including Jewish ones, all accuse Israel of torturing Palestinian prisoners? ” “They do the same thing in America. The Arabs should be happy to be in prison, the food is better than what they eat at home,” he says, still undaunted. What about soldiers shooting children? “It is war, these children are dangerous. They should have just shot about 200 of them, frightened them all. We could have saved a lot of lives. I thank him for the drink and continue on my way. Datya, the public relations person I have an appointment with, is pleasant and cordial. She hands me a brochure, entitled “Gosh Katif: New Zionism plus Torah True Living in Action.” Gosh Katif have a tourist hotel, 3 beaches, 18 tennis courts, and a riding stable. She explains how the Jewish settlements produce 50% of Israeli’s tomatoes in computerized greenhouses, and about their plans to raise ostriches, and build a sausage factory. “Everywhere in the world people use cheap labour,” she says, in answer to my question about the irony of Palestinians picking Israeli tomatoes and labouring on settlement houses. “How much land do Jewish settlers occupy in Gaza,” I ask? “Between 5% and 7%,” she says, pointing to a map on her wall with yellow circles drawn around each settlement. “Why don’t these circles include military camps, the miles of security buffer zones, or the agricultural land controlled by settlers,” I ask? “Because this is all state land, there was nothing here before, only sand.” Is there anything else you want to see?” she asks.

Across the street in the school yard I meet a fourteen year old boy who tells me that “all the Palestinians should go back to Jordan,…and that Palestinian children threw stones at Israeli soldiers “because their parents told them to, and that he “hates Prime Minister Rabin policies, but likes him because he is a Jew…and that he will never leave this settlement because it is Jewish land.

I catch a ride out of Gosh Katif in a settlement vehicle with it’s radio playing Joe Cocker’s “what would you do if I sang out of tune, would you stand up and walk out on me.” At the crossroads I thank the driver, but he says nothing, and turns left towards Gaza, the same way I want to go.

Standing by the side of the road intense heat radiates from the black pavement, but it feels refreshing. My thoughts go back to the words of Dr. el-Sarraj’s father “They will never forget.” I understand them better now. How scarred and afraid people can become. No one is immune, and how right Hanan Ashrawi is when she says, “Violence has to end with the victim.”

The Jews use force and the Palestinians use anger, but they are both victims, and the occupation continues in the West Bank, and Palestinian refugees still sit in camps in Lebanon. Israel remains oppressive and Palestinians continue to resist – each other and themselves. Perhaps Dr. Eyad el-Sarraj had the best solution when he was stopped during the intifada and ordered by a soldier to extinguish the flames from a burning tire with his bare hands. Eyad refused the order and when the soldier threatened to take his identification card Dr. el-Sarraj didn’t protest. “Go ahead, take it, I don’t care” he said. And when the soldier threatened to beat him, Dr. el-Sarraj said, “go ahead, but before you do, I know there is a real human being behind that uniform, and I would like you to show me that person. The soldier got tears in his eyes, he seemed to melt, and then he just walked away.