Meeting Bill Reid, and Making the Lootas

As a documentary photographer I try to engage myself with what is real in the world. To tell stories that need to be told. I take on projects that either really turn me on or really piss me off.

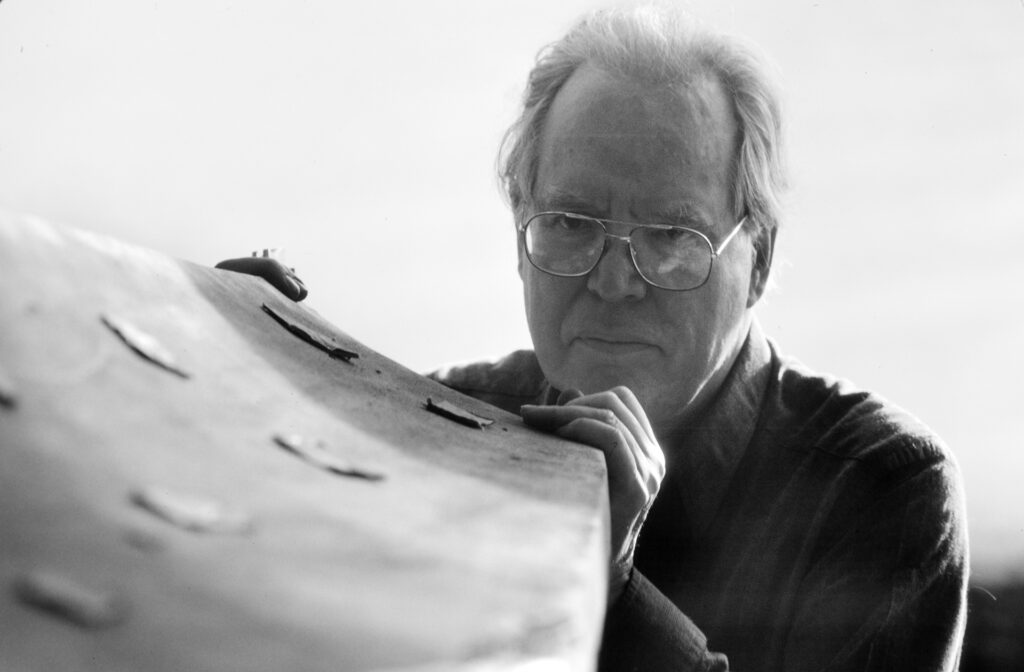

In 1985 a book publisher invited me to document Bill Reid making, carving, the first Haida war canoe in over 100 years. It was to be one of the showpieces of Vancouver’s Expo’86. At the time I had no idea who Bill Reid was, really. I had, like millions, marveled at his monumental sculpture , “The Raven and Clam Shell (First People) featured at the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver. But that was about it until the day I walked into the carving shed on a beach outside Skidegate, Haida Gwaii.

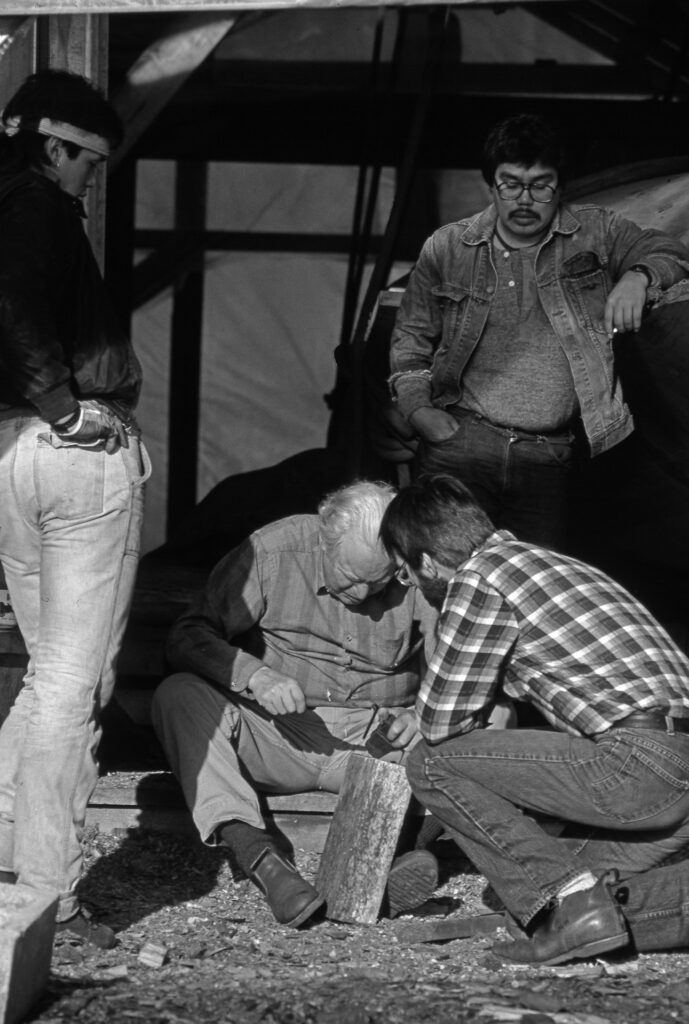

When I walked in I assumed he was the white-haired fellow whittling on a stick in the corner. Are you Bill Reid I asked? The 10 other people in the room all looked at me like I was an alien. Bill seems to like that…that I didn’t know who he was. We immediately hit it off. It was the beginning of a long and lovely relationship. Within a few days he had given me three cheisels and a rough sketch of a spoon on a scrap of hard Yew wood. “Carve this out” he said.

I did and he liked it. He invited me into his world of deep carving as he called it. Carving with intention, where everything is related to everything else. For Bill “happiness was a well-made object”. It is for me too.

During the first three months I spent with Bill making the Lootas, the lessons seemed endless. We, all the carvers, learned by watching Bill, and he understood that the best way to teach people was to show them how you are. When I wasn’t behind my cameras I pitched in with odd jobs Bill assigned to me.

It was a gift that gave new meaning to my job.

I never talked to Bill once about photography. While I was becoming amateur carver, I was also often in the midst of what I will tersely describe as petty politics mixed with soaring egos on all sides. It was as one of the carvers described “a zoo”. Let me put it this way. Most of the time I see my photographs with some kind of redeeming value….they gave voice to people or an issue that needed a voice. What I don’t want my photographs to do is perpetuate myths that only serve a few at often great cost to others.

It added a whole other surprising dimension to my job.

There is always more than meets the eye in a photograph. There is always what was left out. For me it is more than usual. Mostly I can say that my photographs are “authentic” at least I certainly strive for that. In the case of these images I have my doubts. Between the politics and the theatre and the pretense of being too close.

Haida’s are no stranger to transformation. People looking at these photographs could not possibly know the half of it. Meaning….what it is like to carve.

Documenting cannot reconcile what I would sum as the constant current of pety politics that seems inseparable from the great art that comes out of the flames of conflict.

The making of this canoe was a collective effort.

My entry into this realm came the day that Bill gave me a three cheisels….turned out to be far more than just a process of transforming a giant redwood cedar log into a 15 meter Haida war canoe.

Bill Reid was a famous artist when I first met him. I only knew him through the mythology and the press that preceded him. He taught me to carve and the countless nights I spent with him in the rented “A” frame on the outskirts of Skidegate.

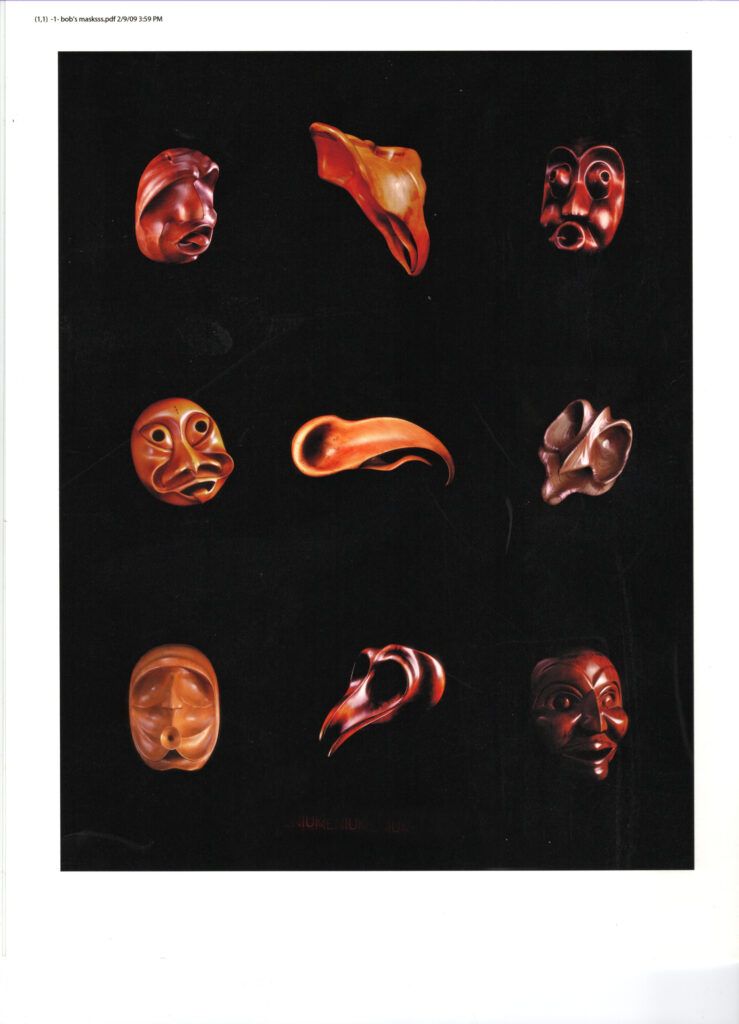

Carving is meditation. There are no mistakes, no right way or wrong way. It involves subtracting wood one chip at a time. What I do on one side, I do on the other, – a perpetual balancing process. I don’t use drawings, or have any preconceived idea of what the finished carving will look like, but I always know where I am going to remove the next chip of wood from. The only rule I have is to try and leave the carving balanced every time I put it down.

I was commissioned, in 1985, by book publisher to document the making of Bill Reid’s Haida War Canoe named the “Lootas” or “Wave Eater”.

This was the first war canoe of it’s size (15 metres carved from a solid red cedar log), made in over 100 years. The early part of the process involved figuring out what tools were needed to do this big carving job. Custom tools, axes, adzes and chisels were designed and forged.

These images span the complete evolution of the Lootas, – from tree felling to launching. As the rough log was hollowed and shaped, it needed clamping to prevent the green wood from twisting out of shape. It was an exercise of measuring, balancing, and leveling a log that was continually changing and moving. The steaming was the most dramatic and critical phase. The long fibers of Red Cedar wood needed softening by mixing red hot rocks, water, and ammonia. In the old days urine was used, instead of ammonia as a softening agent. As hull was slowly pried open, – the bow and stern magically lifted. The steam transformed static carving into a canoe with a beautiful curved hull. The critical time came in determining when to stop spreading the hull. Too much would have split the canoe in half. A series of images show Bill during this very stressful time.

Bob’s Carvings