Tibet

I was in Nepal in the spring of 1987, when the “Freedom Bridge” connecting Nepal and Tibet was opened by the Chinese for only one week.

Myself and a Finnish journalist hitched a ride on a local bus enroute to Lhasa. From there we planned and prepared to be the first foreigners to travel to the secure military zone on the Tibetan/ Arunachal Pradesh border on the Indian border. It took us two months hiking and avoiding military checkpoints. We got arrested just miles from the Indian border, high in the mountains, by a group of young Chinese soldiers, who presumed that we were Indian spies. It was the beginning of yet another saga but the end of our journey to the area where the Indians and the Chinese were actually fighting. We were held in a small military barracks for about a week until Chinese security people arrived on foot, speaking perfect English. They confiscated our passports and we all headed on the long trek back to Lhasa. In the end we wrote out confessions before we were put on a plane out of China to Honk Kong, where both the American and Indian Embassies wanted to chat with us. Our first encounter with the CIA.

My friend Jari wrote a book, in Finnish, about our adventures, called “Kalashnikov Cocktail” and numerous articles. Here is one.

Rumours of conflict between India and China circulate in Lhasa, Tibet under shadow fear

With rumours of fighting with India circulating in Lhasa, the locals in eastern Tibet are again under the shadow of fear.

Jari Lindholm

August 15, 1987

ISSUE DATE: August 15, 1987UPDATED: January 2, 2014 10:53 IST

Chinese soldiers in Tibet

For some weeks now, rumours of an impending border conflict between India and China have been circulating in informed circles. Chinese spokesmen in Beijing have accused India of violating air space, massing troops on the border and “unprovoked firing” and have threatened to teach New Delhi a lesson. Indian strategic experts have warned of a possible Chinese attack and the Indian Government has moved troops and air force fighters to the eastern borders. Finnish journalist Jari Lindholm, accompanied by a photographer, entered China on a tourist visa last month and is the first foreigner to travel to the security zone in the Tibetan border area from the Chinese side. He obtained a firsthand account on the Chinese military buildup and its implications for India. In an exclusive report for India Today, Lindholm provides this eyewitness account.

“The Indians never wanted to negotiate. They violated our air space and sent troops to our territory. Clashes have already taken place, and a major offensive will start soon.” The chief of security in the town of Miling in Eastern Tibet is a big cheerful man with a loud voice. He is in charge of nabbing Indian spies along the Sino-Indian border a few miles from the McMahon Line, an area disputed by China and India for 40 years.

“We are presently concentrating troops on the border, and so are the Indians. War has been in the air for month s, and our patience has worn thin,” says the security chief. Rumours of fighting and air strikes have for several weeks been circulating in Lhasa, the Tibetan capital. In the wastelands of eastern Tibet rumours become facts. Tension is obvious. The sound of big guns echo daily in villages near the Tsangpo river security zone.

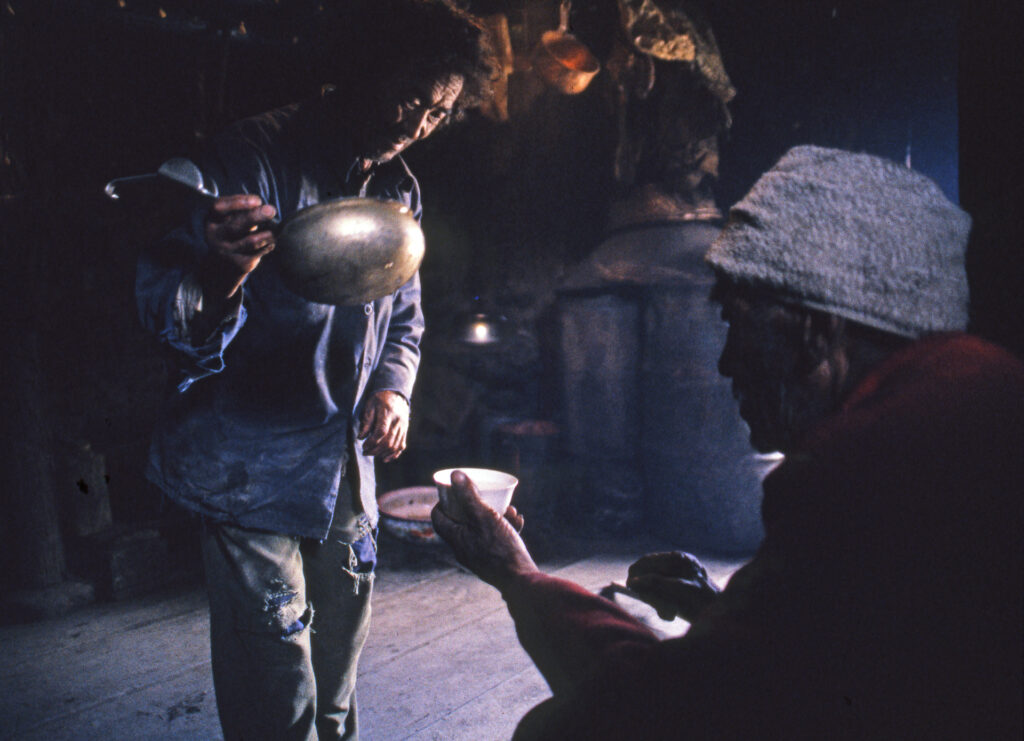

Tibetans working: Under suppression

The firing is too close to the border for it to be artillery practice. Troops, weapons and fuel in convoys of 70-80 trucks surge to the military bases in Bayi and Zetang. American-made Sikorsky Black Hawk helicopters fly regularly over the valley of the Tsangpo river to Metok, where most of the Chinese troops from the eastern garrisons are said to be stationed. Anti-aircraft guns guard the confluence of the Nyang Chu and Tsangpo rivers.

New roads have been built all over south-eastern and south-western Tibet. The supply route leading south from the town of Zetang towards Tawang near the Bhutanese border is almost blocked by heavy military traffic. Tens of trucks carry ground-to-air missiles from the north, and camouflaged ambulances drive on the busy streets of Zetang.

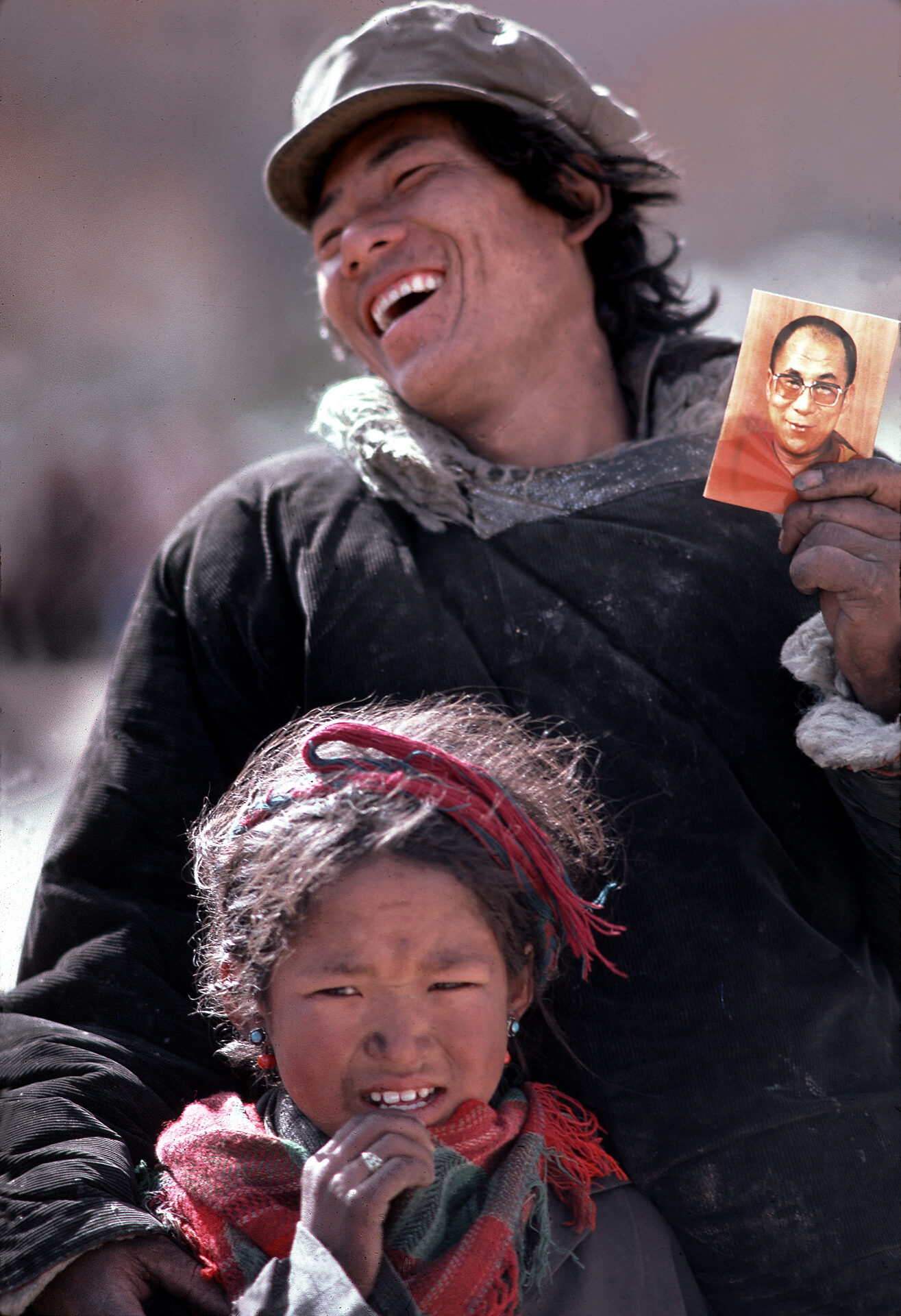

Tibetans in Lhasa: Palpable tension

The south bank of the Tsangpo is closed to outsiders. Heavily-armed Chinese soldiers patrol the Tibetan villages and practice target shooting in the woods.The atmosphere is tense. The Tibetans of Miling are afraid of being caught in a cross-fire: the Chinese fear that Tibetans may welcome Indians as liberators. The security zone of Tsangpo has been cut off from the rest of Tibet. Two years ago villagers crossed the river in yak skin boats or by the ferry at Lusha village, but all traffic has long since been terminated by the authorities.

Lusha is in a sensitive area. The village previously existed on both sides of the Tsangpo river but, in the late ’60s, the Chinese forced people to move from the northern to the southern side as an added defence against “Indian infiltrators” through the Lusha La Pass.

The Chinese seem anxious to keep the clashes secret. This is easily achieved in an area so mountainous and densely forested. The Tibetans have learned to keep silent, and Chinese suppression condemns them to turn in foreigners travelling without permits.

The policy of secrecy has resulted in a wave of rumours resounding even in Lhasa. Young English-speaking Chinese in the Tibetan capital claim that they have already been asked by authorities to act as interpreters for Indian prisoners of war. They are eager to fight India.

Kong Po Bon Ri mountain is strategically situated near the confluence of the Nyang Chu and Tsangpo rivers. On the south side of the Tsangpo, a Chinese army supply route runs west towards the military centre of Zetang. In the east is Lusha La Pass, an old refugee route to Arunachal Pradesh in India.

The sound of heavy artillery fire can be heard almost daily from Metok in the south-east and Tawang in the southwest. Nobody in eastern Tibet wants to talk about fighting, and the army has orders to arrest all foreigners in the area. Local villagers are told by the military and the security police that every stranger is a potential spy, most probably an Indian.

A strictly controlled security zone has been created parallel to the Tsangpo river. Even the locals are not allowed to cross the river without a special permit. Rumours of war travel fast, and the repressive measures taken by the authorities have resulted in a paranoid atmosphere.

For the villagers, the bad days are back in eastern Tibet. Local villagers have lived under constant threat of Chinese atrocities since February, when regular troops were moved to the Indian border and frustrated trigger-happy youngsters were left in charge of the garrisons. Young soldiers have robbed travellers, beaten villagers and harassed hermits in remote caves.

Local officials are not interested in filing charges against the military, and villagers feel helpless. “Soldiers just walk into our homes and demand food and drinks,” said one villager. “They steal our valuables and insult our women. All we can do is keep out of their way.”

One evening, the monks and nuns of Sekhora, a tiny commune of meditators on the holy Kong Po Bon Ri mountain in Eastern Tibet, congregated outside their abbot’s cave. Like every night for 30 years, it was time for evening prayers.

Two Chinese soldiers stepped from the shadows. They were young, short-tempered and armed with revolvers. They ordered the monks to disperse and dragged the abbot to his cave. One of the soldiers tied the old man up, the other one put a clip in his revolver and pointed the gun at the abbot’s forehead.

A pilgrim rushed into the cave begging for mercy. “Save the man,” the pilgrim begged. “He is just a simple-minded monk.” The soldiers looked at each other. The other one pointed his gun at the pilgrim and screamed: “In the name of the state, we confiscate your belongings.”

The pilgrim relinquished his possessions – 25 Yuan and an old wrist-watch. The soldiers threw him out of the cave and pistol whipped the abbot. The old man survived with bruises and a bloody nose. This was not the first time he had suffered in the hands of the Chinese military. Because of his religious commitment, he was jailed for 12 years during China’s Cultural Revolution in the ’60s.

Tibetans try to forget the tension, but it seems impossible. Loudspeakers in the Chinese garrisons blast political propaganda and ear-splitting military music day in and day out. Villagers crossing the bridge over the Tsangpo river without a permit are likely to be beaten by Chinese guards with AK-47 machine-guns.

The chances of a beating increase if trespassers happen to be Khampas – the tribal warriors of Tibet who are especially despised by the Chinese because of their rebellious arrogance.

Monasteries on the holy mountain have been cut off from the villages. “We have been told not to discuss the war even with other monks.” said the abbot of Sigyal Gonchen monastery.

“With villagers we can chat about weather and crops but talking about clashes on the border is considered to be spreading rumours.” Another monk added, “We don’t use our southern cave any more. It is impossible to meditate when guns go off all the time.”

The north bank of the Tsangpo river is silent and hostile. Every village has its informers and party members, and people fear for their lives. The Chinese garrisons are almost empty. Snot-nosed youths in ill-fitting uniforms loiter around canteens harassing passers-by or playing basketball. Their comrades have been moved to the front.

Villages between the garrisons have been vacated and are now veritable ghost towns. The village of Lithing is practically empty. When we asked for a boat ride across the river, women and children ran away in terror and doors were slammed in our faces. Dogs barked in rage behind closed gates. In other villages we were told that the men and boys of Lithing had been forced to the south side of the river to cook and haul water for the Chinese troops.

Finally, in the village of Bana, an old man reluctantly agreed to ferry us across the river in his yak skin boat. The next morning he arrived at our camp obviously confused. The night before, the public security had visited him and politely threatened him about the serious consequences he faced if he helped the strangers.

That night the security police paid a social call to our camp-fire. They congenially told us to beware of poisoners. “Villagers are known to have poisoned travellers in order to get their power and good properties.” said a policeman. “Do not buy or eat anything from the locals. Go back to where you came from.”

Disregarding all the diplomatic threats, the old man hastily took us across the river the next morning. On a portage over one of the many sandbars braiding the river, the boatman indicated his throat would be slit if he were caught by the Chinese. His fear was reminiscent of the late ’60s when Tibetan villagers scared for their lives were forced to destroy their monasteries and most valued religious possessions with dynamite and fire.