Among the Inuit

I cherish the summer when I first camped with Paulosie Attagutalukutuk’s family of nine in a canvas tent on Baffin Island. We ate raw seal liver on the sea ice and cracked open caribou legs to slurp out the marrow. I arrived a stranger, and left with new tastes and deep respect for my Inuit friends. It was a good day when other Inuit came to our camp and joked about me, the “qallunaaq”, the white man, and Paulosie told them that the “qallunaaq” had travelled with them for a long time, that he hunted and ate raw meat and was like a member of the family.

The lessons were endless. Being lost, not knowing how to get back to Igloolik, whether at sea or on land, was a common condition, for me. For Paulosie, however, everything was familiar. He was home. He belonged to the land more than the land belonged to him.

This is what led me to Igloolik, over thirty years ago, – to document people who live on the edge of habitability. I found a big difference between “settlement life” and “being on the land. People were different on the land. Happier I thought. Ami Panimera, an old friend once told me “we don’t belong in houses”. But the fact is all Inuit now live in houses. One old fellow I know is considered kind of ‘crazy’ in town, but when he is out on the land he is considered one of the best hunters around. He surprises even his relatives.

Caribou hunting involves driving around in boats, or snowmobiles, stopping often, looking for signs, walking up to high places to better scan the tundra for movement. One time, during the darkness of December, while hunting with Andy Attagutalukutuk, Paulosie’s eldest son, we came upon the frozen entrails of three caribou. On closer inspection with my flashlight I could see how diligently the ravens had pecked away at the rock hard piles. Andy tells me that these caribou were shot two weeks ago. He names the hunters and tells me who their relatives are. Earlier we stopped where he said his father always found caribou. And before that was a place where a friend’s grandparents lived a long time ago, and before that was the place where his cousin shot a polar bear last year. Like his father, Andy’s arctic is mnemonic and intertwined with history. Each place has meaning that is inseparable from the stories and experiences attached to them. And when I ask Andy how he knows where he is going, he simply says, “I follow my instinct”.

Late one summer, we were in Foxe Basin in Andy’s motor boat, when fog, ice, and darkness came. After a few stops and maneuvers to push ourselves between the huge ice flows, my curiosity about Andy’s ability to navigate in fog, at night, with not even a wisp of wind to give him any hint of direction, gets the better of me.

“Where are we?” I ask. Andy slows the boat, and with a huge smile on his face, he says, “I don’t have any idea where we are.” We laugh. Is it a joke? I ask. “No,” Andy says, “I really don’t know where we are, and I’m laughing because you don’t believe that we are lost. Do you know how to use a “GPS”?, he adds, pulling a Global Positioning System instrument out of an old sock from his food box. Andy informs me that he used his GPS only once, about a year ago, and that the batteries might be dead, and that the instructions are at home. He then stretches out and soon is fast asleep. Waves lapping against ice break the dead calm of the icy night sea. Then I hear the awesome sound of a bowhead whale breathing, very near us. Andy snores. He destroyed his dog team three years ago because it too much work to hunt seals to feed them, when he would rather hunt caribou. He joked about how Rebecca, his wife, thought he was spending more time with his dogs than with her.

Going onto the land was a way to touch the earth with people who put profound meaning on this connection. Making the photographs was a good way to do this. Now, they are fleeting reminders and memories that bind the heart and land. Archetypical connections from a long way back that are more than they appear. They represent places I don’t live in, but that my soul yearns for. Places where the dictates of the forbidding ecological niche that the Inuit ancestors occupied presented few options for survival. Where hunting successfully and living with the weather were the preoccupations of everyone. Where permanence and accumulation were not practical or sustainable states. Where clothing and shelter were temporary, that came and went like words and ice or tools that belonged to whoever needed them. Places that require pragmatic skills, like hunting, the ability to trade, and where a willingness to share meat determined social status, and success was measured by wisdom, not wealth. And where, after everything else has gone, the experience remains, and my life changed forever.

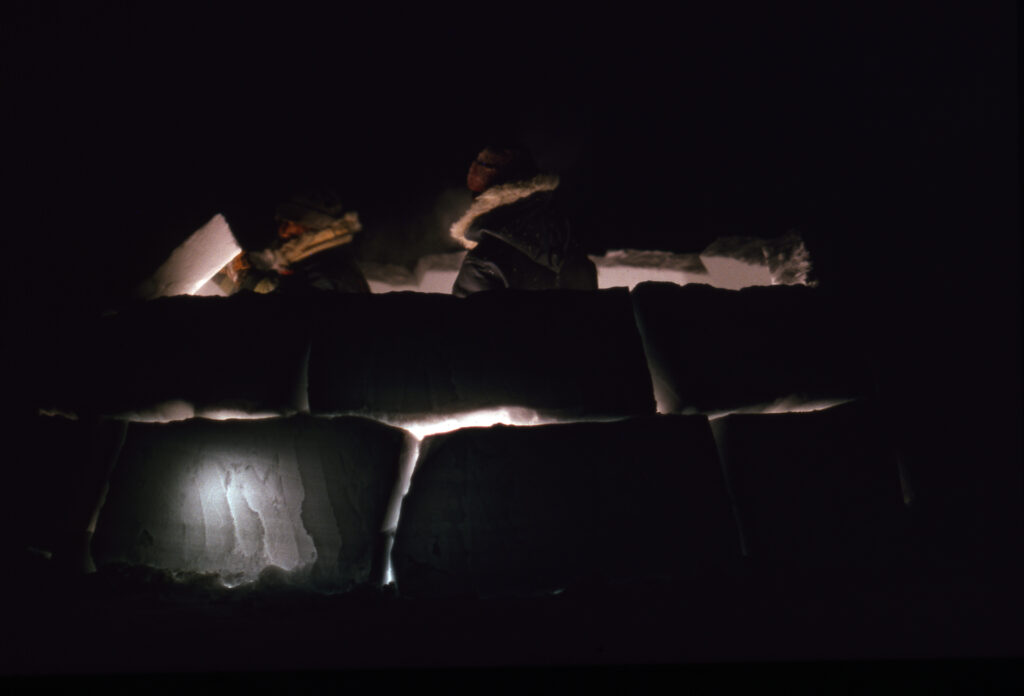

Camping, for months at a time, I was only alone when my eyes were closed. In the privacy of my own thoughts I could easily imagine Inuit living four-thousand years ago, in frigid darkness, always vulnerable, close together inside a crowded igloo, tent, or sod house, and how sharing everything led to deep respect for the sanctity of one’s own thoughts. Thoughts were one of the few things considered to be personal property, and easily violated by questions, disagreement or analysis. Typical “qallunaaq” or “white man” questions about “when” and “how far” are irrelevant, and simply receive a shrug. One does what has to be done – no matter how long it takes. One morning in a summer camp, I felt compelled to apologize to Andy, for not helping to slide the boat, using caribou heads for skids, into the water. Looking surprised at my comment, Andy replied, “It doesn’t matter if you take pictures while we carry the boat, everybody does what is necessary.”

Paulosie often stopped his boat for reasons which escaped me. I remember one night while we were lying on our caribou-skin beds having a conversation, I asked Andy why we stopped in the boat so often, and he said he did not know the reason. “Why don’t you ask your father then?” I asked boldly. “To ask why,” Andy replied simply, “is a stupid question. He would think it’s a stupid thing to say. I know he has a good reason for what he does, and if he wanted to tell me, he would.”

In Inuktitut, one’s thoughts are called “Isuma” – a rare abstraction in a tangible world. Except for about 60 of the last 4,200 years of Inuit habitation here, cooperation, sharing, and a cunning alertness to the spatial qualities of their environment, proved more useful than ownership, accumulation, competition, and even the concept of time. Living on the edge of habitation, these were all foreign concepts to a culture oriented to the present and the concrete. Perhaps it should not be surprising that the suicide rate among Inuit is over 8 times the national Canadian average.

For me these photographs from are graphic reminders of connections that I believe are imperative to a more sustainable and enlightened world. My biggest fear with publishing these images is that they will be seen to perpetuate myths, and prolong romantic notions about the Inuit, that serve only to numb us from the truth about them, and ourselves. There is already far too much propaganda in the world, bad beliefs. My hope is that these photographs will be seen as tools of enlightenment rather than entrancement, which keeps us stuck in this modern, but comfortable “dis-ease”.

Whenever I look at the sea ice I am surprised that anything, even polar bears, can survive out there. I think about time, distance and scale, and how a footstep doesn’t take you very far here. When I feel the icy wind bite my face, I remember what Martha Naqitarvik’s sister Koonoo from Arctic Bay told me one time between stories of shaman, cannibalism and connections with the land. “I think the world around us is hearing. That is why the wind has stopped… And if we stop talking. The wind will come back”.

Igloolik, 1998

Bowen Island, 2021