0%

A landmine awareness sign on a main road near Wazir Hospital, Kabul. In Afghanistan, 65% of all landmine casualties are civilians. Since 1989, when the United Nations began mine clearance here, over 3,000 indigenous deminers have been trained. About 1% of the estimated total mines have been removed from half of 118 square kilometres of priority areas like roads and bridges.

Kandahar, Afghanistan. A 35-year-old father and deminer is paid about $150 a month - or ten times the average wage here. He is one of 24 deminers working to clear this 42,000 square metre area. The team has worked here for twenty-six days, and expect to finish in twenty more days. Eight landmines are found today, making a total so far of 103, plus 25 unexploded mortar & artillery shells, and 47,825 metal fragments.

When 5 kg. of foot pressure detonates this Russian-made “PM-4” landmine containing about 240 grams of TNT, the explosion shreds the trigger leg, macerates skin and muscle, and fires bone fragments, clothing, shoe, dirt, and debris deep up into that leg, and often into the genitals, arms, and eyes of the victim. Landmines are designed to maim.

Before surgery, Leong Leg's wounds are washed. His father thinks that the landmine that maimed his son was recently planted. "But I don't know by whom," he says, speaking to me outside the operating room. When I ask if he knows any other landmine victims, he replies: "All five of our neighbors have had problems with landmines."

Cambodian surgeons amputate the remains of Leoung Leg's charred right leg at the knee. They repair his compound-fractured left leg, and clean out puncture wounds to the rest of his body. Severe secondary infections often affect landmine victims, whose highly contaminated wounds require specialized surgical techniques.

Orthopaedic Centre, Maputo Central Hospital, Mozambique. Eight years ago, when Zaida Ernesto Bahule was four, the ground exploded. "My mother told me if in a little while she did not answer me when I called to her, it meant she was dead." Zaida lay beside her dead mother for three days before help arrived.

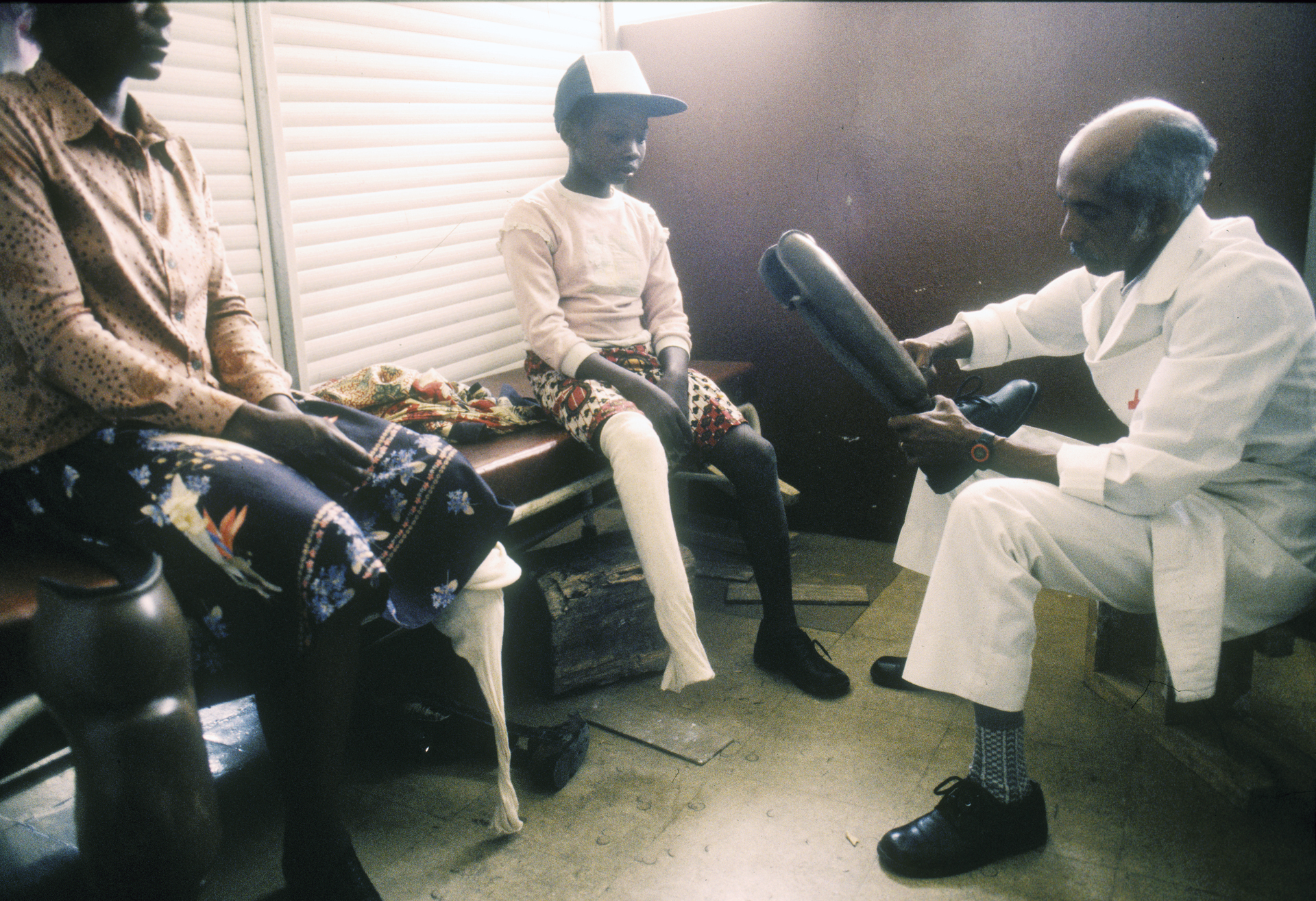

The exercise room of the Orthopaedic Centre, Central Hospital, Maputo, Mozambique, where technicians manufacture and fit artificial limbs, and teach patients how to use them. More amputees would be using this facility, says the centre's director, Max Deneu, "except that most people don't have the means or the money to get here."

Battambang Civilian Hospital, Battambang, Cambodia. An estimated 110 million anti-personnel landmines, planted in sixty-four countries, are responsible for killing or maiming seventy people every day. Victims, especially unmarried women, are often treated as economic and social outcasts and have little hope of employment or marriage.

The United Nations estimates that removing the world's active mines would cost between $33 and $85 billion. Learning to live with landmines is vital for everyone, but especially children. Members of the Afghan demining agency (OMAR) regularly offer landmine awareness classes at the mosque in Chargala Village, near Kabul.

National Landmine Awareness Day, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Working since November 1993, deminers in Cambodia have been able to clear about twenty square kilometres of a total of 2,138 square kilometres of land suspected to be contaminated with landmines. Over forty kinds of landmines from fifteen countries have been found in Cambodian soil.

Ghallauden, 29, blinded while demining, is led by his nine-year-old son, Commander, in Herat City, Afghanistan. "I was tired and pushed my prod harder than usual. It was a PMN that got turned on its side, or the Russians planted it that way. After the explosion picked me up and threw me down hard, and I realized what had happened, I started feeling my hands and counting my fingers. I felt them gone."

Orthopaedic Centre, Wazir Hospital, Kabul, Afghanistan. Wazir Hammond, age nine, requires prosthesis refittings every six months. He rests against a wall of sandbags that protect the hospital against rockets, shelling, and bombs. An estimated 10 million landmines pollute nearly 500 square kilometres of land in Afghanistan.