Shatila Field Notes

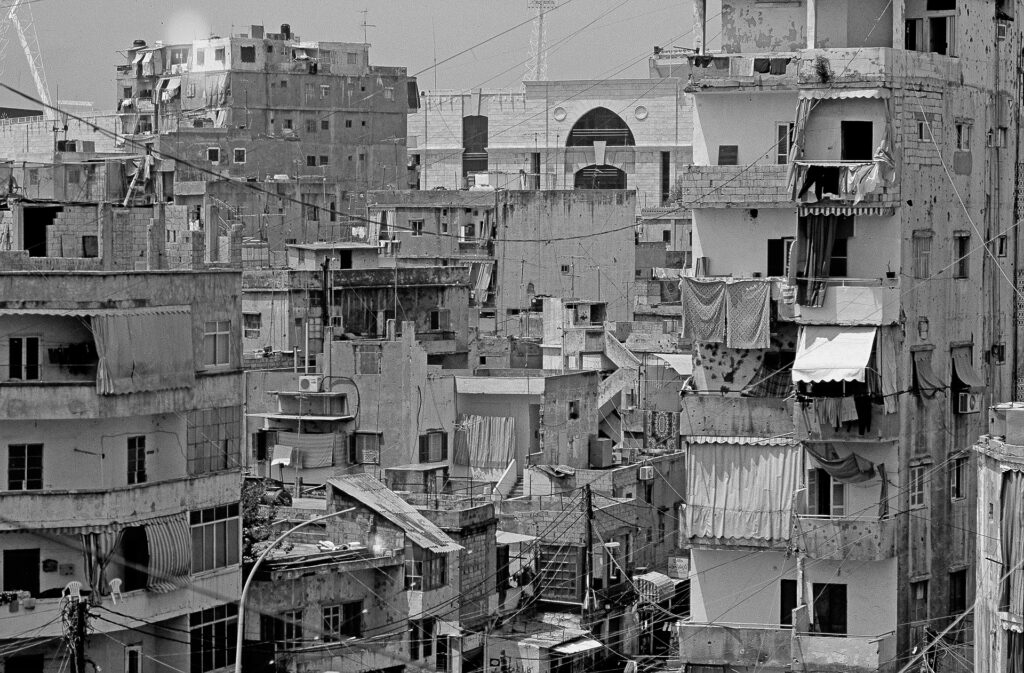

Seeing Shatila, gives me a whole new perspective on what I thought about Somalia being the most brutal war I’d seen, or Angolans the most starved, Afghans the most displaced, S. African’s the most racist, or Palestinians in Gaza the most humiliated. At the entrance to Shatila, the rancid stench from garbage piled up for a city block behind the Syrian-run market stalls, makes me gag and vomit up most of my strong morning coffee. I feel like I am entering a slab of concrete 7 stories high with one alleyway through the middle and a thousand narrower passage ways leading to the lives of some estimated 20,000 poverty stricken, disenfranchised, war hardened, suffering and traumatized people. And where all this “disease” erupts is in the hearts and minds of the children who have consumed 54 years of dedication to the Palestinian cause, and all that this implies.

I was there when the people of Bedawa and Shatila marched in memory of the 54 years that they have lived in these hellholes. One man carries a key to his house in Palestine, and I photograph a child who carries a Palestine Mandate land registration certificate as proof of ownership of the land that was taken away from her family, 54 years ago. “We thought we would only be gone for a couple of weeks” one man tells me.

As Nadia Salameh my 50-year-old guide explains, the children here are more “Palestinian” than their parents are. The visual evidence comes from a visit to a kindergarten where the teacher, Amira Baytau, works everyday, and is lucky to have a job. If you don’t work for one of the NGO’s in the camp, or the Palestinian Red Crescent Society, you don’t work because Palestinians are not allowed to work (in 72 jobs/professions) in Lebanon. She is 21, was born in Shatila, and lost her entire family, everyone…. to the war and the massacre in 1982.

The children sing songs and hold up a poster they have made. This is one of 5 kindergartens in Shatila, and each one has approximately 100 children. The poster is a painting of the Temple on the Mount in Jerusalem, and on each cloud in the sky is the name of each child in the class and where their home is in Palestine. Places they have never seen, places many of their parents have never seen, but places they call home and know all about, and they are only 5 years old. We will be the flowers of Palestine…says another poster on the wall….We have the right to speak, to play, and be heard. I ask 5-year-old Abdu Hadi where he comes from and he tells me Akba in the north of Palestine. Another small child tells me she is from Haifa and another says Rashid. None tell me they are from Shatila.

At the UNRWA school where class sizes soar to 50 students per class, I ask Amanda, a 12-year-old, what she wants to be when she grows up…. she tells me “I want to kill Israelis”…I want to be a pilot…of a war plane…but then there are other pilots that have the right to take their parents on trips….

Nadia takes me along the narrow dirty alleyways. It is hot and high noon, the only time the sunshine creeps through the slit at the top of this seven story concrete canyon. Out the big metal door of the kindergarten, I step into one of the long, narrow, alleyways – all netted together by a web of electric and telephone wires, water pipes and hoses, dripping and hanging and protruding from the graffiti-plastered, often bullet riddled, suffocating concrete walls, with few windows. Water and electricity is patchwork, expensive, more or less illegal and interrupted on a daily basis. Hezbollah pays for the daily water delivery truck. The confusion of wires speaks loudly for years of re-wiring. And my imagination runs rancid with all the bloody horror that has happened here. The playgrounds are the war-torn buildings. Places of death and memories that never go away. “My grandfather was killed here.” “My mother, my sister, my brother died here….For every house I visit in Shatila there is another story of death and destruction.

Fatima Mahjoub, for example, was a twenty-year-old mother when the massacre occurred twenty years ago… She remembers Israeli bombs striking a nearby building. Her husband went outside to see what was happening….She stayed in the house with her children who were 2 & 3 year old at the time. A few minutes later a women came to her house…”What are you doing here” She said…”They are killing people all around”.. Fatima pushed her son and daughter out a back window…a very small window…”I don’t know how I did it” she tells me…”It was so small.” She just ran, and found herself lost in the narrow alleys, just following people that were running and trying to get away. There was shooting…She ran to the PRCS Gaza Hospital a few blocks away.

Days later she found her husband who had his own tale of the massacre… When he went back to the house, the military had occupied it. They asked him about Palestinian fighters and beat him. He thought he was going to die. He had seen many people dead in the alleys. Fatima’s sister and brother in law ran to the Kuwaiti Embassy (which is about 4 blocks away). Israeli soldiers where all around the Sports Stadium…. My sister saw Ariel Sharon talking to a South Lebanese soldier. During the Israeli bombing my sister lost a leg and her husband is still an invalid from his wounds.

Nadia Salameh was born in the two-room cinder-block house that she continues to live in. Her son is unemployed and her daughter, Abeer, is a schoolteacher in Denmark, and another one works in the kitchen at a kindergarten in Sweden. She also has another son, Walid, who works as a mechanic in Sweden. They send money to Nadia every month. She is also very lucky to have a job with Palestinian Red Crescent Society (PRCS), for the last 20 years, making $500/month.

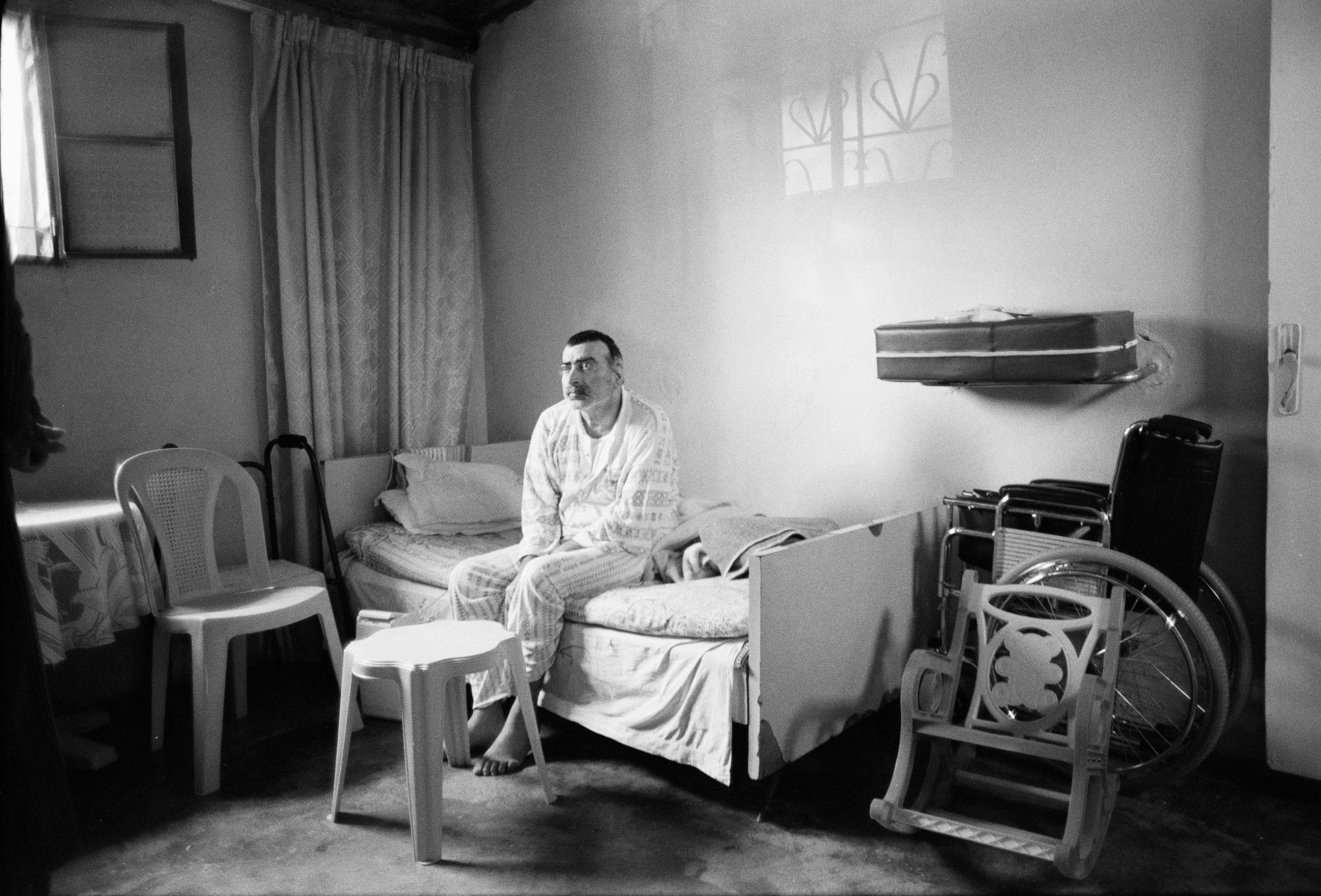

Mahmoud Mustafa lives in Bedawa now. He has four children…two sons and two daughters. He was born in 1948 in Borj Shemali Camp near Tyre where the Israeli army massacred 130 Palestinians in 1982…They were killed in a shelter near the sports club. He was in the camp at the time of the massacre. He moved to Bedawa in 1985 because his family had a house there. He suffers from Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Mahmoud cannot work, or earn any kind of a living. The family gets help from relatives abroad, some food from UNRWA, government committees and some NGO’s. He is despondent, has fits of violence, and has had drug abuse problems in the past. His 18-year-old daughter recently got married and his 14-year-old son is learning to repair refrigerators and washing machines…. His medication costs $35/month. Fatah gives him $20/month, and his neighbor also helps Mahmoud and his family.

One cemetery in Shatila is the site of a mass grave where uncounted Palestinians are buried…some on top of others. I take a few photographs of a banner spread between two trees that depicts Ariel Sharon as a Nazi…The gardener who tends the flower beds hands me a rose from one of the many little bushes that he nurses….”They came and killed my family”…. “I was wounded and crawled under their bodies.”

Abu Hammid Khaireddin Mohsin, 51, was born in Shatila and was blinded by a Lebanese policeman when he was 17. His first of three sons was three months old when the Israelis invaded in 1982. They lived in the same house, but on the bottom floor. “Israeli tanks were firing from nearby the Kuwait Embassy and the Stadium.” “On the morning of September 17th, a cousin of mine came running here and told us that his son was just killed in the street… He asked if my wife would go to the street and bring the body of the 18 year old boy.” His wife went out onto the street and was hit with machine gun fire from a tank, “that’s how she lost her leg.” His wife, Fatima Ghazauu, 37, slowly lifts here dress so I can see her prosthetic leg, and the bullet hole scars on the other and tells me how…. “An old man named Jamil Sarris was helping me when they shot and killed him.”

Abu Hammid continues to explain how “after a while some youth brought the body of the boy wrapped in a blanket.” Then Fatima interrupts with an explanation of how it was 3:00 in the morning on September 18, when someone finally took her to the PRSC Gaza hospital. “My husband was back home with his 70-year-old mother and out 3-month-old daughter, hiding in a corner of their building, he had no idea what had happened to me until he got news days later. It was very difficult even to find enough to eat during the war. Our son is twenty now and has epilepsy.” Years later, an N.G.O. sent Fatima to the U.S.A. for a new, better fitting and lighter, prosthesis. We come from Kasayer village near Haifa in Palestine,” she says. “We refuse to be refugees in Lebanon or any other place” says Abu Hammid, “I will live in Palestine, even if it is in tent because there is nothing better than people having their own nation.”

I meet Abeer, a young 21-year-old very modern looking, beautiful young women, who dreams of moving to Canada with her boyfriend who is an engineer. Her father’s home is now called Karyet settlement. I hear again, and again about how the electricity explodes because of the pressure, how some people have generators, how it come and goes everyday, how there are 50 students in a class at the UNRWA school, and how there are no playgrounds. She worries about her family, six in all who live in a crowded house. “There is no security here she says…There are some very bad people here and the Lebanese military cannot enter Shatila.” She went on to ask, “Who is protecting us…No one. We are forgotten about.” She answers herself.

As I go with Nadia, through the alleys, and in their homes…The stories pile up…The names are different but their stories are all of horror, humiliation, poverty, torture, and suffering…